|

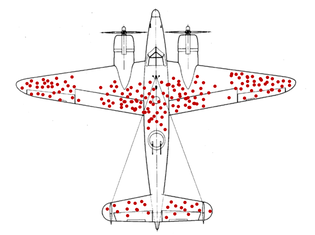

Reading time: 6-8 minutes The announcement by eLife to do away with formal accept/reject decisions has caused quite a stir. One of the major claims of the eLife announcement was: “By relinquishing the traditional journal role of gatekeeper and focusing instead on producing public peer reviews and assessments, eLife is restoring control of publishing to authors, recovering the immense value that is lost when peer reviews are reduced to binary publishing decisions, and promoting the evaluation of scientists based on what, rather than where, they publish.” I've underlined a couple key points in that statement. If you haven't already, I'd recommend reading my 5 minute take on the eLife announcement for full context. But I'll just dissect these two points here: 1. "eLife is restoring control of publishing to authors" "Restoring" is a weird word isn't it? Since when have authors had control over publishing? I would argue that, even in the era before modern peer review (pre-1970ish) authors still didn't have control over where they published. In my last article, I made a point about how this is, in part, because experts need to be accountable to other experts (authors, reviewers, or editors). But even ignoring that, strictly from a marketing standpoint, there's no point in human history where an author could effectively disseminate their work - fiction, academic, or other - without the aid of a publishing house. Darwin didn't print, bind, and distribute all his own copies of "On the Origin of Species" any more than Harper Lee ran the printing press to produce every copy of "To Kill a Mockingbird." And neither of them saw to all the intricacies of marketing their work, distributing it, or filling orders. "But we're in the internet age. We have social media for dissemination and we can even use LaTEX or rely on algorithms (e.g. bioRxiv web versions) to typeset our work." That's true. It's a fair point. But social media is only really effective if you start with a following. There are tons of stupid cat videos on the internet, but the ones you're most likely to see are coming from just a few famous channels. Don't forget survivor bias: for all the social media success stories out there, there are tens of thousands that completely failed. And the ones that succeeded are often propped up by shout-outs from existing prominent users. Take it from me, fun fact: I used to run a skateboarding trick tips YouTube channel back from 2007-2011: the early days of YouTube. I was even successful enough that my "How To Ollie" video came up before Tony Hawk's. But I was only successful because I produced videos that were half-decent at a time when YouTube was devoid of content. Were I to start my channel today, I'd be lucky to reach even a level of fame best described as "obscure." So why do scientists think disseminating their work by social media is any different? Why do scientists think that they can start a Twitter, reddit, Facebook, post a link to their few hundred followers and "boom!" their work is out in the world! Sure, some preprints take off like wildfire. But that brings me to my second point... Reading time: 5 minutes

For another perspective focused more on the issue of asking readers to do even more to navigate the "fire hose of information" spewing at them: a good piece by Stephen Heard Let me start by saying: the new eLife model is bold, and I am a big fan of eLife. I do not think it will be the end of the journal. I don't think it should even tarnish eLife's reputation much. In fact, I think I like it. But that's because, as far as I can tell, eLife has simply traded "hard" power for "soft" power in editorial decisions. Now I do have a concern with the very direction eLife is heading: I think it's bad for the health of science. I think it's a push towards the death of expertise. Contrary to many, I like journals. I even like journals I hate. I like them because they're expert authorities, and the world needs expert authorities. This isn't about the pursuit of an idyllic science publishing landscape, it's about the nature of science communication to human beings, which last I checked, describes me aptly. It's about how we maintain accountability over information flow, over scientific rigour. I like the eLife proposal precisely because eLife has... in reality... hardly done anything. But all the pomp in the announcement they've made is a direction I do not want to see science go, and one I think is genuinely dangerous. With that said... So I hear eLife announced a thing? Yes, yes dear reader they did. Here's some important context before we get into the announcement (from: link):

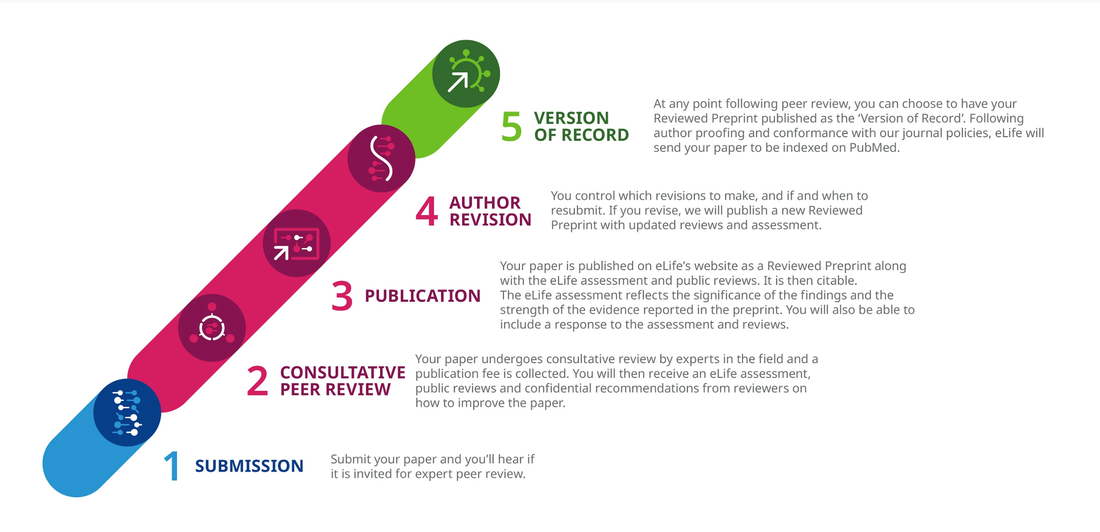

So what did eLife announce? Here's the jist (from: link):

Two comments: Point #1: Effectively, editors now have the power to desk-accept papers before they're even sent for review. Just think about that as we continue re: gatekeeping. Point #3: I have not seen near enough acknowledgement of this in the public discourse. The fact that there's an editor statement within the article itself means that regardless of whether one reads the reviews (99% won't), there is an up-front assessment of the work attached. |

AuthorMark Archives

July 2024

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed