|

Reading time: 10-12 minutes In this article:

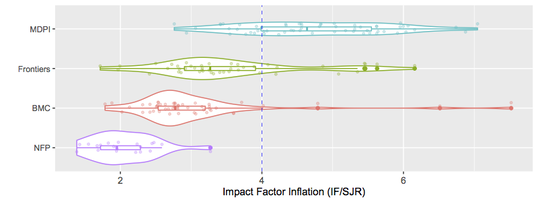

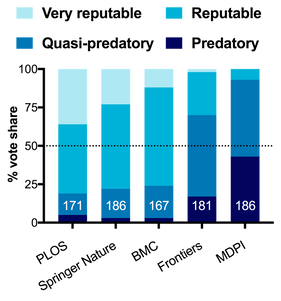

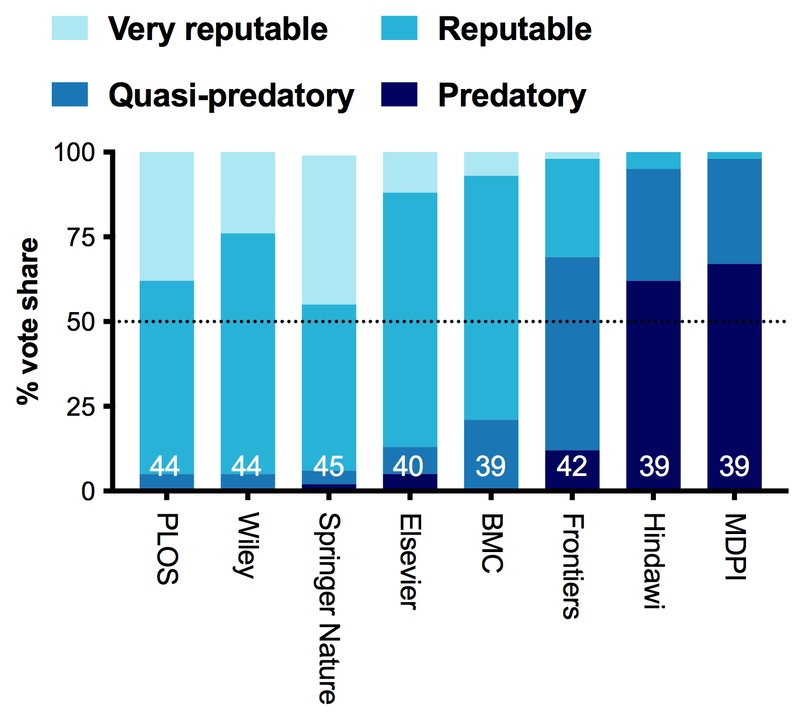

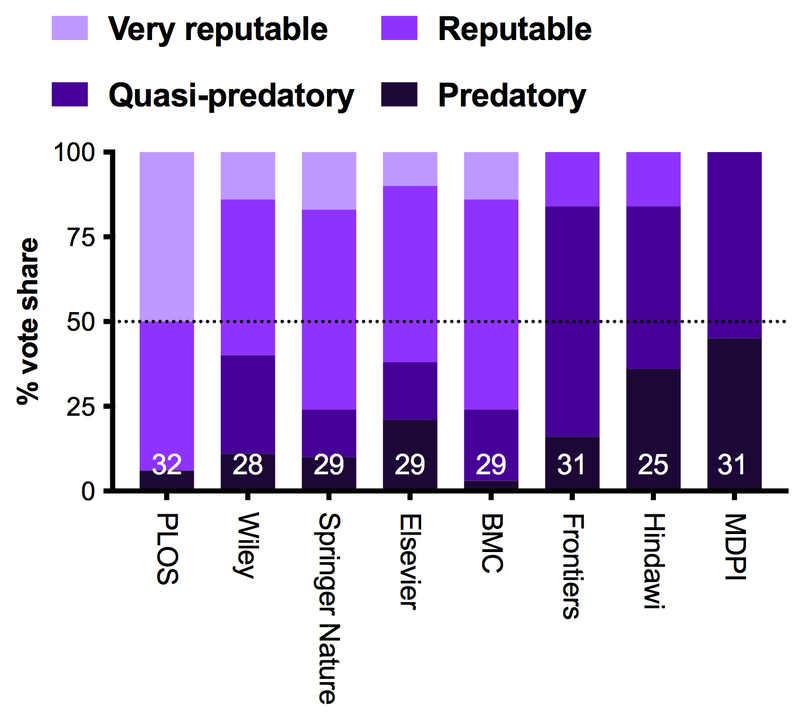

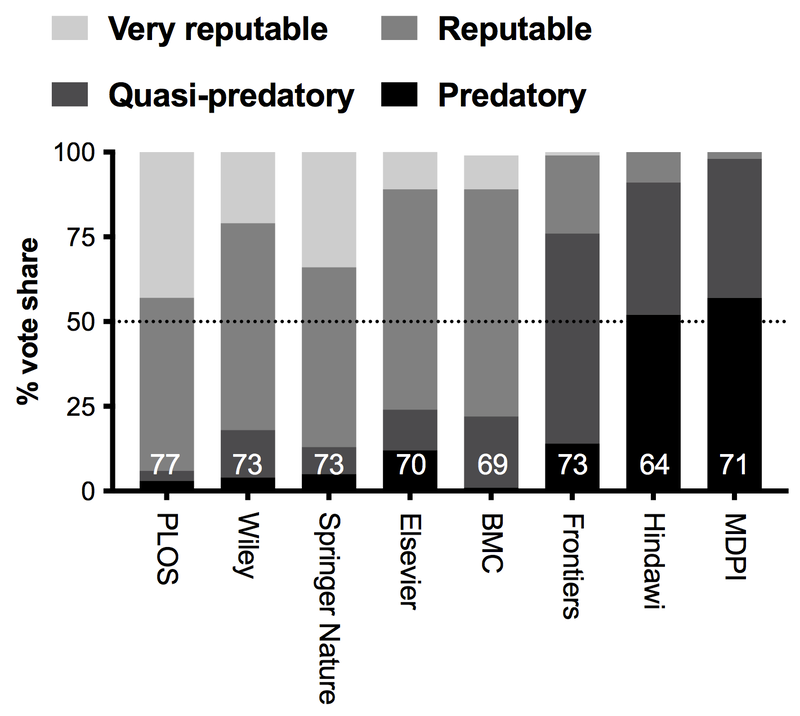

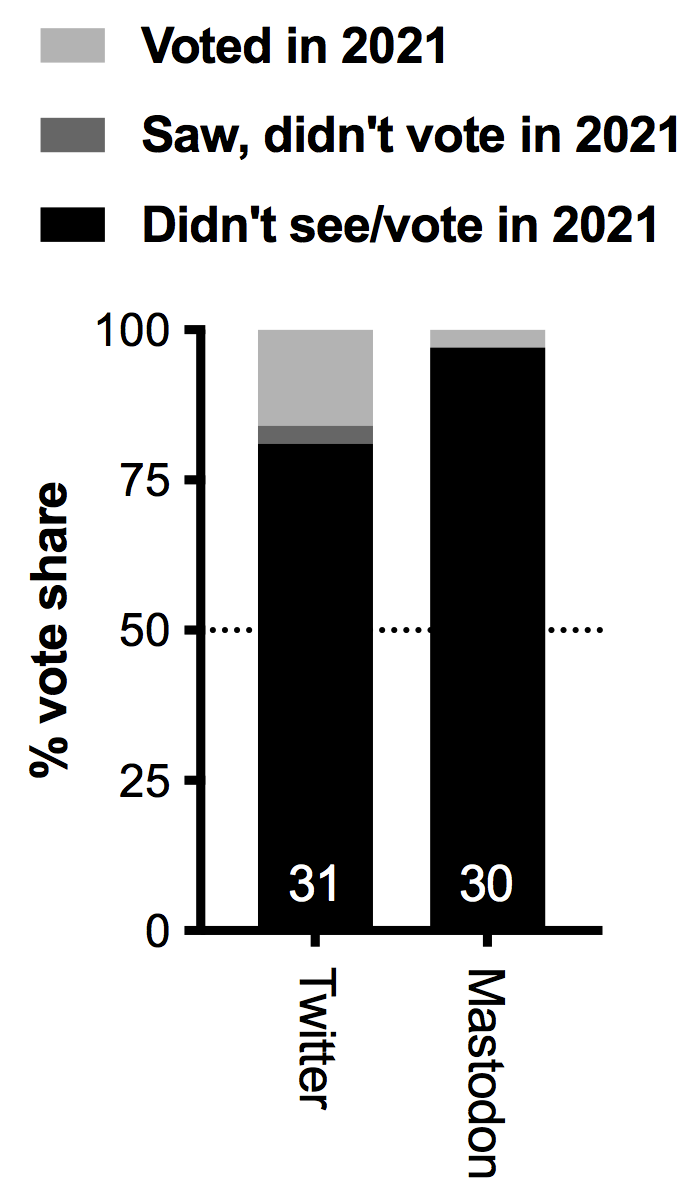

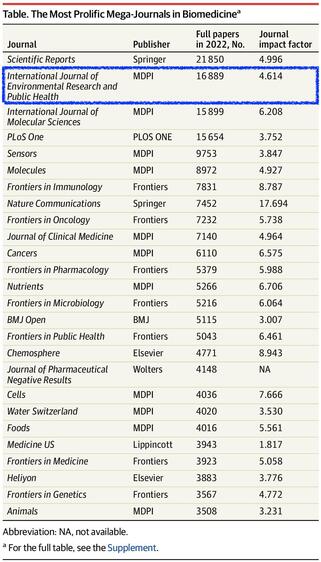

Edit Mar 25th 2023: moved Twitter vs. Mastodon tangent to "p.s." section A year ago I wrote a blogpost called "What is a predatory publisher anyways?" In that post I looked at the origin of the term in 2012, and what it meant at its inception. I held a Twitter poll, gathering ~175 respondents from across the spectrum that asked people's opinions on whether various publishing groups were "predatory." SPOILERS: I just redid the poll in Jan 2023 on both Twitter and Mastodon. The aim of that poll was not only to get a sense of publisher reputations, but to look at what are the behaviours of publishers that people associate with "predatory publishing." What did I learn in 2021? Well... not exactly what I expected (fun!). "Predatory publishing" is an overly-vague term When I held those polls, I expected a few things, and was surprised by others: 1) I expected groups like Frontiers Media and MDPI to have higher proportions of "Quasi-predatory/Predatory" votes, because those publishers have reputations of poor academic rigour, a history of controversial articles, and are even boycotted by world-ranked international universities for the purpose of assessing academic job performance [1,2]. 2) I expected a non-profit publishing group like Public Library of Science (PLOS) would be universally agreed as "Reputable." After all, how can a non-profit be called "predatory?" How could their work possibly be viewed as 'feeding on prey'? Yet ~20% of respondents felt PLOS was "Quasi-predatory/Predatory." 3) The proportion of folks calling Springer Nature and its subsidiary BioMed Central (BMC) "Quasi-predatory/Predatory" was about the same as PLOS! Surely if some folks are just jaded with publishing in general, you'd expect that the for-profits wouldn't be viewed with equal disdain as the not-for-profits? But I was wrong, because the term "predatory" is pretty vague. What is a predatory publisher anyways? While there's a general correlation between certain behaviours and public opinion on who qualifies as a "predatory publisher," it's also pretty clear that the term has no universal meaning anymore [3]; I'm not sure it ever did, to be fair. Still... I was curious to see how perceptions might have changed over the last year, given sustained negative (or at least, controversial) press about publishing groups like MDPI [1,2,4,5]. So I asked the same poll again on both Twitter and Mastodon, expanding the list of publishers in the poll. I also asked folks to indicate if they'd seen/voted in the poll a year ago, to better know if the final result might be biased by pre-existing impressions. Results below! Figures: poll results from Twitter (top left, blue), Mastodon (top right, purple), merged results from both Mastodon and Twitter (bottom left, black), and the proportion of people who had seen the 2021 polls on either website (bottom right, black). Sample size per poll is indicated in each column in white numbering. In total, there was an average of ~42 responses per publisher on Twitter and ~29 on Mastodon. Merging both polls, ~71 votes were cast per publisher in the Feb 2023 polls. 81% of respondents on Twitter hadn't previously seen the 2021 Twitter polls, while 97% of respondents on Mastodon hadn't seen the 2021 Twitter polls. In general, the previous poll in Dec 2021 likely had little impact on the results in Feb 2023. Last time, as mentioned, a whopping (and in my opinion, surprising) ~20% of respondents said the not-for-profit PLOS was "quasi-predatory/predatory". This time, very few folks said PLOS was "quasi-predatory/predatory" across both Twitter (4.5%) and Mastodon (6%). That's more in-line with the expectations I had from 2021! If only I hadn't revised my worldview with cynicism due to the 2021 results, I could have acted all smug... but no I was surprised yet again. The world isn't so terrible after all... But just as interesting, most of the trends were the same: a clear majority thought PLOS, Wiley, Springer Nature, Elsevier, and BMC were broadly "reputable," while a clear majority thought that Frontiers Media, Hindawi, and MDPI were broadly "predatory." Given the results from 2021, and the broad agreement and progression clear in 2023, there are a few publishers that clearly do not have the endorsement of the scientific community at large. Let's talk about that, and let's talk about why. Moving past the word "predatory" There are a few academic bodies that contribute to a publisher's legitimacy. For instance: 1) Are a publisher's journals indexed in databases like Web of Science (Clarivate Analytics) or Scopus (Elsevier)? 2) Do a publisher's journals typically have impact factors (Clarivate)? Are they notable in other journal rank metrics (e.g. SciMago Journal Rank, "SJR"). 3) Are that publisher's journals ranked 'well'? whatever that means... 4) are they members of scientific bodies like the Committee for Publication Ethics (COPE)? But academics clearly care about some of those qualities more than others. For instance, all the publishers I included in the polls are members of COPE. Yet three of them have reputations where the majority think they're at least somewhat predatory. And while MDPI journals have fairly high Impact Factors (IFs), I think the broad community is realizing how publishers can game the IF system, and so being ranked "well" does not always mean being ranked high. I previously proposed a metric to judge how appropriate a journal's rank is, by dividing each journal's Impact Factor by its SciMago Journal Rank (IF/SJR), which correlated very nicely with the 2021 Twitter poll results. A high IF/SJR indicates a journal has an inflated IF rank compared to its actual utility (according to SJR, see notes on this methodology here).  The ratio of IF/SJR correlates well with community perceptions on how "predatory" a publisher is. NFP = Not-For-Profit journals, BMC = BioMed Central, Frontiers = Frontiers Media, MDPI = Multidisciplinary Publishing Institute. The lower quartile of MDPI is indicated by a dashed blue line as a benchmark for judging if any individual journal has an inflated IF/SJR. So let's try to define what it is that motivates people's opinions a bit better. In my previous article, I gave an in-depth explanation of publisher behaviours that are somewhat "predatory." This time around, let's introduce some terms to better discuss what is meant by "predatory publishing," and by the end, my hope is we'll have a better way to discuss what exactly is a "predatory publisher." Predatory publisher This is an umbrella term for a few different kinds of publishing groups/journals. I've divided predatory publishing behaviour into three subsets below: Vampire press (also see "vanity press" - end of article) The "vampire press" is a term coined by Ian Bogost in 2008 (earliest use from what I can tell). Ian used it in a way much akin to the more common vernacular "vanity press", which helps authors publish articles/books largely for padding their CVs and nothing more. The phrase "vampire press" never took off, but I love it, and I'm going to take it and adapt it. Here, I'll define a "vampire press" as a publisher that drains its victims (authors/editors) of time and funds, offers little of actual value, but remains reputable on the surface. Often this works by instilling a sense of brand loyalty among authors. Thus, when authors encounter critics, they are faced with the choice of acknowledging that their work is associated with a disreputable publisher, or ardently defending that publisher's reputation because their work is now associated with the brand. They become "thralls" of the vampire press. Of the publishers included in the polls above, I'd say MDPI is the most emblematic of a proper vampire press. Poll after poll confirms MDPI's reputation is abysmal, with the vast majority of respondents calling MDPI at least somewhat "predatory." And yet, MDPI is experiencing massive growth in total articles published, and high (and highly inflated) journal ranks according to Impact Factors. MDPI performs cursory peer review at best, emphasized by their ridiculous article turn-around-times: only ~37 days from submission to acceptance (including revisions!). All other publishers take 2-3 times that long, minimum [4,5]. MDPI argues this is simply because they've trimmed all the fat from the process, and MDPI is just super efficient. But it's pretty clear that their methodology is leading to crap articles being published under the MDPI banner (as expected [6]), as the broader research community judges them to be of poor character (see polls, IF/SJR). And yet, at least in 2021, I found plenty of folks who would vehemently jump to the defence of MDPI (often invoking "whataboutism"); MDPI is good at making thralls. Update March 25th 2023: in March 2023, Clarivate (Web of Science) de-listed one of MDPI's signature journals for editorial concerns: the International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health (IJERPH) [7]. For context, this journal publishes more articles annually than PLOS One [8]. This follows two world universities (U. South Bohemia [1] and Zhejiang Gongshang University [2]) having already rescinded faculty support for MDPI journals, and told their staff that MDPI publications won't count towards academic assessments. I emphasize MDPI here because unlike, say, Hindawi, MDPI isn't just a "vanity press", it's a proper vampire. Aggressive recruitment of authors to associate with the brand, regardless of the brand's reputation, is what makes a "vampire press" effective. Rent-seeker / Rent extractor I'm borrowing this term from Paolo Crossetto [4], with perhaps a different emphasis. Per Wikipedia: "Rent-seeking is the act of growing one's existing wealth by manipulating the social or political environment without creating new wealth." The best analogy for rent-seekers in academic publishing are those publishers who take advantage of the authors at the whim of "publish-or-perish." They offer authors quick and easy outlets for their research... at a price. Now... the fees of rent-seekers aren't always exorbitant, and any journal charges publication fees. What makes a publisher a "rent-seeker" is how aggressively their business model relies on petitioning authors for articles, which they then host, taking in all the profit at almost no personal cost. Rent-seekers flood your email inbox with special issue invitations - they manipulate the academic environment to siphon wealth without creating more. The two most obvious rent-seekers in the above polls are Frontiers Media and MDPI. Both journals have made it their de-facto business model to publish articles as part of "special issues." Both publishers flood academics with invitations to host their own special issue, get recruited editors to spam their colleagues and other academics with invitations to contribute articles, and then even have automated systems to invite arbitrary reviewers by algorithm if the editors are taking too long. It honestly reminds me of a summer job I had in college working for Vector Marketing (makers of CutCo knives). Let me explain: Vector Marketing works by giving their employees a set of kitchen knives, and then they ask employees to make their own in-home appointments to sell the knives. The knives are of decent quality, if expensive, so it's not as if CutCo is selling a defective product. But the company itself doesn't have a list of potential customers, and you're not allowed to go door-to-door. Instead, they ask employees to ask their friends/families to invite them into their home so the employee can do a Cutco knives sales pitch. What's insidious is that they avoid telling would-be employees exactly how the system works until AFTER those employees have completed training and committed to the job. All of that is technically legal, but it's pretty scuzzy. Rent-seekers are doing the same thing to well-meaning academics. They get them to propose and edit special issues, get those editors to recruit all their friends to submit articles (often not under the terms editors assumed would be there), and then take all the profits for themselves. Authors are left drained of funds, editors are left drained of time and emotion, and all anyone has to show for it is a product no one really asked for in the first place (even if the quality can be decent... sometimes). Despite extremely similar business models, somehow Frontiers Media hasn't taken the extra step that MDPI has. Again, in poll after poll (and supported by IF/SJR data), Frontiers is en route to being labelled a "predatory publisher" by many... but they're just not quite bad enough that people are willing to call them outright predatory. The objective difference I can think of between the two is the article turn-around-time [5]. If Frontiers is doing something to stave off being fully denounced as "predatory", it's probably the fact that their peer review process takes a normal amount of time. To quote the inverse of Dan Brockington [6]: "Patience may not necessarily fix mistakes, but it makes fixes more likely." Importantly, rent-seeking behaviour in and of itself has nothing to do with article quality. I was actually a little surprised, and disappointed, to learn that Proceedings of the Royal Society B has adopted the practice of rent-extraction. This is a journal with a rich history dating back almost two centuries!! And yet there I was, with an email in my inbox effectively saying "Hey, you know that preprint you put on bioRxiv? Despite probably spending months, years likely, generating data and writing it, I bet you haven't thought at all about where you'll publish it, right? Hey, name's Proc... Proc B. Can I buy you a drink?" What's especially disappointing is that the Proc B office seems to think cold-calling thousands of manuscripts in order to get just a fraction (<10%) of them to submit to Proc B is somehow good for their reputation. But as mentioned, Rent-seeking behaviour has nothing to do with article quality itself: In fact, Proc B actually rejected ~70% of the articles that it itself solicited authors to submit! I'm honestly relieved by that, as it's evidence that they're maintaining their editorial standards. But I find it really unfortunate that such a prestigious journal is begging for bioRxiv's table scraps. Am I crazy to be disappointed in Proc B's rent-seeking behaviour? Is this just me? It's a key question because the answer determines what we tacitly approve as acceptable publisher behaviour. Would we be ok with this behaviour if it wasn't Proc B? If so, why should Proc B get a pass? Do we want a future where unsolicited invitations to submit are to be taken seriously? Scams The final category is short and sweet: it's a scam. These publishers are offering a product they can't deliver. Universally agreed-upon predatory publishers like OMICS publishing group and Bentham Science are example scam publishers. Even if they technically format articles, even if they technically send emails asking for peer review, they do not actually peer review up to academic standards. In some cases, they have even failed to uphold the bare minimum asked of the academic publisher code of conduct set out by COPE: and let's not forget that publishers everyone labels as "kinda predatory" are nevertheless members of COPE. These publishers are so disreputable they lack the vampire press ability to generate thralls. Their continued business model relies on rent-seeking behaviour, but without the intent to conduct even a scuzzy form of legitimate business. For the record: if you've never heard of these groups, OMICS has genuinely been served a cease-and-desist letter by the United States government [8]. Bentham, on the other hand, was advertising fake (and inflated) Impact Factors on their website last I checked a year ago. Oh... but just for the record... Bentham Science is a member of COPE. Are you shi- Conclusion Last time around I think the article got a nice bit of attention because it had a solid poll, asked a question in an unbiased way, and maybe made for a good primer for some folks. My conclusion at the time was that the phrase "predatory publisher" has value in these discussions, because even if it's vague, we still know the connotation of the words. I still think that's true, that having a universal phrase with a clear connotation is useful. I wouldn't say the solution is to abandon the term. Instead, if we can bother to agree on terms like "vampire press", "rent-seeker", and "scams", then I think we can start to have more nuanced conversations about predatory publishing behaviours. For instance: are all rent-seekers "predatory?" Cheers, Mark References

Edit March 25th 2023: this section was moved to be a post-script discussion, so as to avoid going off on a tangent mid-article. Twitter vs. Mastodon: largely parallel results... largely... Unless your name is Wiley, and you're on Mastodon? This was a really interesting aspect of doing the dual polls on both websites. Mastodon is a community with a certain bias to it: it exists because it's made up of people who left Twitter after Elon Musk's takeover (for... reasons...). Mastodon is made up of a subset of people who felt a certain way about a controversial subject. It's expected their opinions will skew from those remaining on Twitter (people who made the opposite decision). In the case of Wiley, opinions differed: while only 5% of respondents on Twitter called Wiley "quasi-predatory/predatory", a whopping 40% did on Mastodon. I'll throw in my personal take here and say: I don't actually know why Mastodon thought Wiley, specifically, was a somewhat "predatory publisher." I'd be fascinated to hear your feedback in the comments section of this post, especially if you were one of those mavericks (no judgement, just curiousity)! In general, Mastodon tended to be a bit more harsh towards established publishers: Wiley was the most extreme difference (a 35% swing), but Springer Nature (18% swing) and Elsevier (25% swing) both have worse reputations amongst the Mastodon community. Really interesting example of how your info chamber may colour your perceptions... But just as interesting, most of the trends were the same: a clear majority thought PLOS, Wiley, Springer Nature, Elsevier, and BMC were broadly "reputable," while a clear majority thought that Frontiers Media, Hindawi, and MDPI were broadly "predatory." Given the results from 2021, and the broad agreement and progression clear in 2023, there are a few publishers that clearly do not have the endorsement of the scientific community at large. Let's talk about that, and let's talk about why. Hindawi as a vanity pressHindawi is so obscure that its poor reputation hardly dissuades academics from publishing with them. Indeed, Hindawi wasn't especially on my radar in 2021, and I don't find myself inundated with invitations to special issues in Hindawi. But I can't deny that I personally viewed Hindawi articles as... putting it diplomatically... "unlikely to be of value to my research." Hindawi seems to exist solely to earn profit off research submissions where the only individuals that read Hindawi articles are the authors (thralls) who themselves publish in Hindawi journals. And since Hindawi generally keeps its head down, fewer people actually care. In this way, Hindawi is also a classic "vanity press."

Comments are closed.

|

AuthorMark Archives

March 2024

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed