|

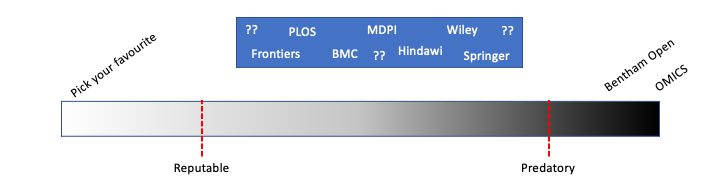

Reading time: 5 minutes TL;DR: we need to talk about predatory publishing publicly. This means defining 'control' publishers that are definitely predatory. Only then can we have a meaningful conversation about where more ambiguous controversial publishers sit on the spectrum. Silence equals consent - qui tacet consentire videtur Let me start with a thesis statement: "The most significant issue around predatory publishing today is the fact that no one is talking about it." At this point, I think most scientists have heard of 'predatory publishing' (if you haven't, read this). But I would say very few can actually name a predatory publishing group, particularly if the verdict has to be unanimous. To be honest, I only know of a couple famous examples of unambiguously 'predatory' publishing groups: Bentham Science Publishers and OMICS publishing group. It seems like we all have a sense of what a predatory publisher is. However the term is so poorly defined in the public consciousness that actually identifying a journal/publisher as "predatory" is extremely difficult. It is a conversation we are not used to having, which makes it very hard to use this label for anything. There are numerous reasons for this:

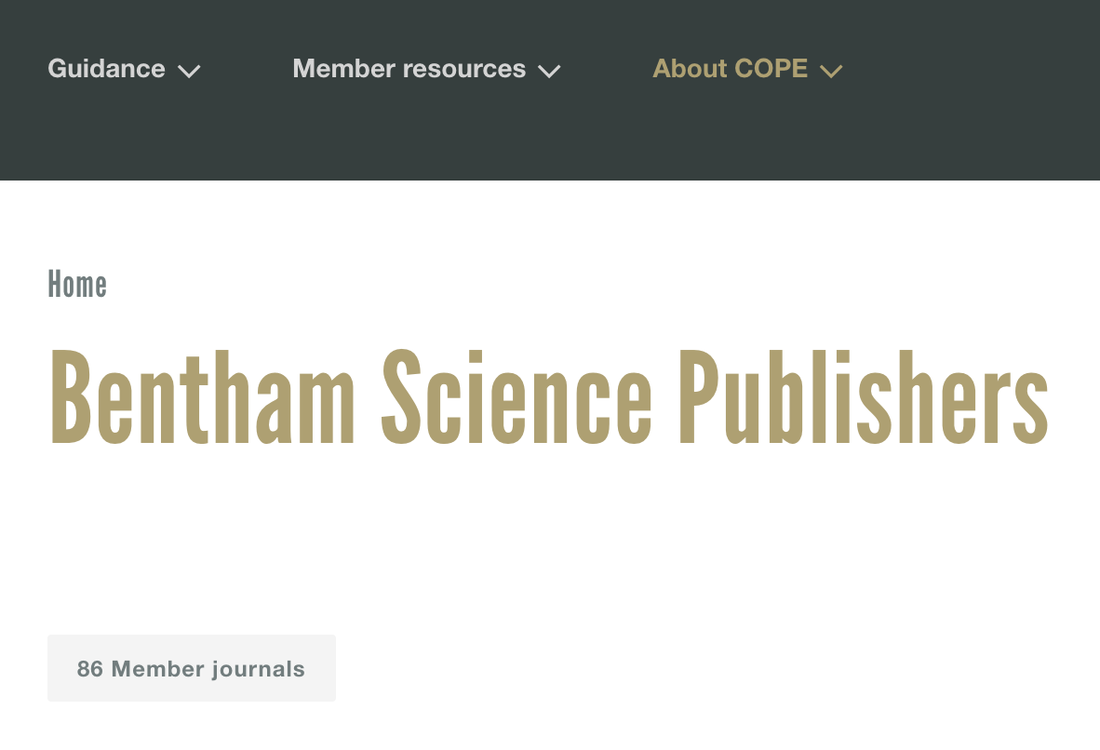

The resources we give to budding researchers are inadequate This may be a controversial opinion, but hear me out: I actually think scientists are pretty smart. We're trained to be critical thinkers, and to seek out evidence to support or reject ideas. That means we don't just trust a random email saying "we were so impressed by your recent publication [INSERT TITLE HERE]." Most scientist's initial state is skepticism. This means we will try to find objective information about whether a journal is legitimate. We'll peruse the website to see if it looks professional, and many of us jump to check for things like if the Impact Factor 'seems legit' (i.e. is too high to be a 'bad' journal). The reason we're so attracted to metrics like Impact Factor is because they offer objective data, and for some godforsaken reason some people view simply having an Impact Factor as if it's a gold stamp of quality. [Insert obligatory praise for SCImago Journal Rank here]. But beyond these basic sorts of checks, very little info is out there to objectively assess if a journal/publisher is reputable. One can go through a laundry list of boxes to tick: does the journal have an ISSN number? Is it indexed by Clarivate and Scopus? Is the journal a member of COPE (the Committee On Publication Ethics)? What about the OASPA (Open Access Scholarly Publishing Association)? These are all fine questions, but I will contend here: this is toothless advice. I already told you: scientists are actually pretty smart. Any journal not meeting these benchmarks is likely already failing in a number of obvious ways (grammar, professionalism, etc...). With big business in the publishing world, websites are slick and professional, and automizing the copyediting process is so approachable bioRxiv is planning to do it for preprints now. And believe it or not, it's relatively easy to get an ISSN, indexed by Clarivate/Scopus, or even become a member of COPE. Getting an ISSN is not a seal of quality, it is the bare minimum needed to reach the starting gate. The hard work of becoming a reputable publisher starts AFTER you get your ISSN/indexing/COPE status. Hell at the time of writing, 86 journals from Bentham Science Publishers are members of COPE, despite Bentham being one of the rare unanimously agreed-on predatory publishers! (Eriksson and Helgesson, 2017). Existing resources on predatory publishing are bland. Library websites warning about predatory publishers are mostly speaking to undergrads, not to mature researchers. They are trying to teach students how to verify information and think critically, asking sets of yes/no questions that can be ticked off a list. This is perfectly good to help budding scientists enter the conversation, but it creates an expectation that a journal is 'good' so long as they can tick all the boxes. Unfortunately, the leaders of the predatory publishing conversation are not ticking boxes: they're trying to decide what exactly are the boxes we should be asking students to tick. And that part isn't easy. But here's my final contention: the reason it's not easy is because predatory publishing behaviour lies on a spectrum, and we haven't defined how far to the left or right one needs to be to become truly 'predatory'. Even when we have, we don't disseminate that information in a standardized way. I ask you legitimately: did you know Bentham Science Publishing / OMICS were widely recognized predatory publishers? Heck Bentham and OMICS are a key reason the Open Access Scholarly Publishing Association (OASPA) even exists (and why it's mind-boggling that they remain members of COPE) (Eriksson and Helgesson, 2017). What can we do about it? A big reason it's so hard to have this conversation is because predatory publishing exists on a spectrum, and no one has defined clear benchmarks for who is and is not a predatory publisher along that spectrum. So let's define that spectrum here. If you are teaching about predatory publishing, if you are responsible for training students to spot predatory publishers, give them concrete examples. Tell them, unambiguously, that publishers like Bentham, OMICS, or IGI Global are universally understood to be predatory journals (yes I've got more examples - for bonus marks d(^_^)b ). Tell them how the United States NIH sent OMICS a cease and desist letter for deceptive practices (Kaiser, 2013). Tell them how Bentham's reputation for sham peer review became so widespread that it helped inspire a collective of other journals (OASPA) to say "we're not like that guy" (Eriksson and Helgesson, 2017). And then get them to research these groups! Give them an assignment where they have to investigate a publishing group (e.g. MDPI, PLOS, Wiley) and then get them to write a report on how that group compares to others. Ask them where they think those publishers fit on the spectrum. Ask them why. Get them thinking early, and give them benchmarks for comparison. "The first time someone dives deeper into what exactly is a 'predatory publisher', it's often the same time they're being courted by one." So let's give students and young researchers a benchmark to compare against. Only then can we begin to have constructive conversations about when other publishers are bordering on 'predatory' behaviour (see: "What is a predatory publisher anyways?"). Cheers, Mark p.s. if you are an educator interested in preparing a lesson on predatory publishing, feel free to get in touch via the "Contact" page. I would be very interested to help design lesson plans for different levels in teaching this subject!

Comments are closed.

|

AuthorMark Archives

July 2024

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed