|

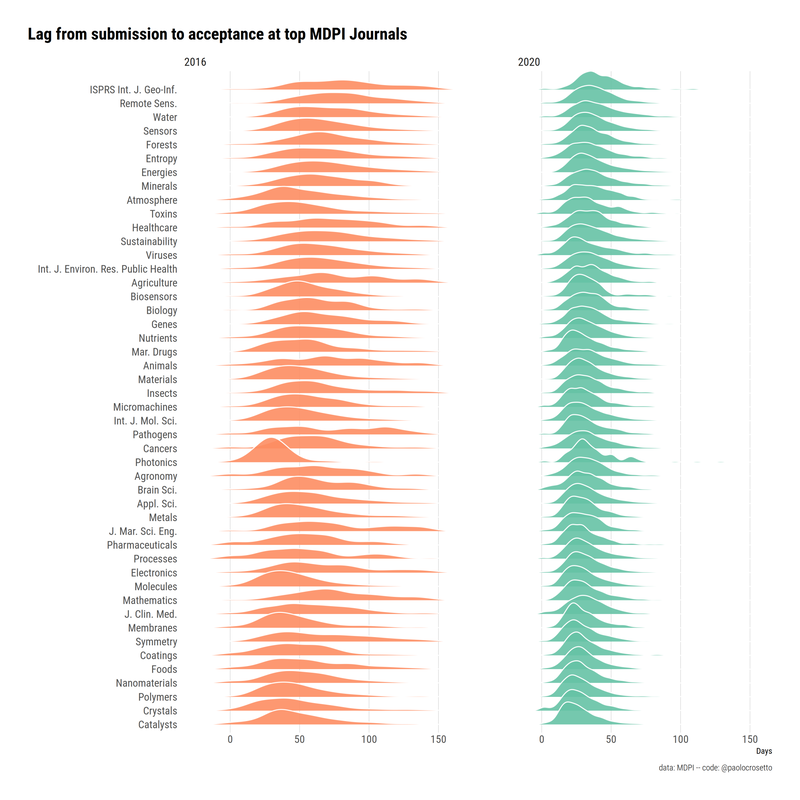

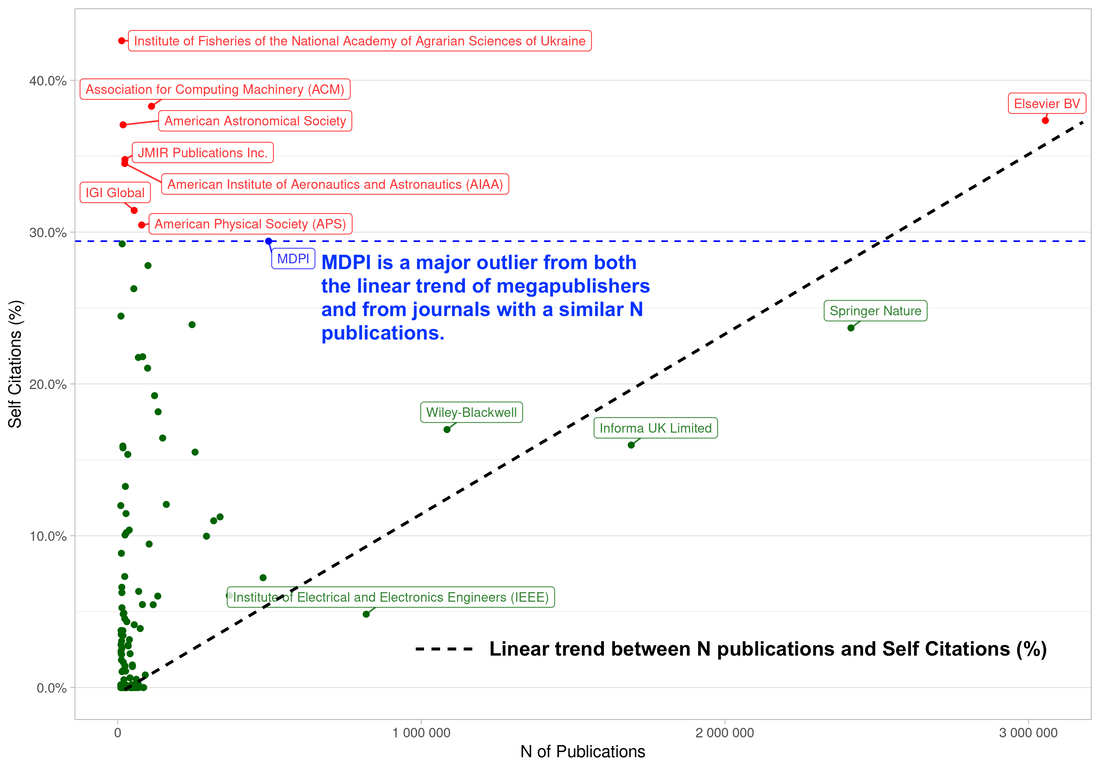

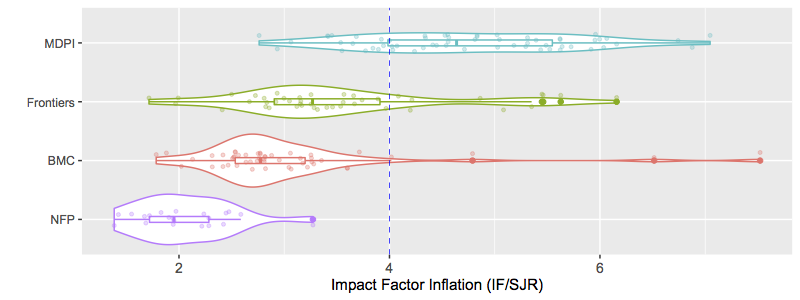

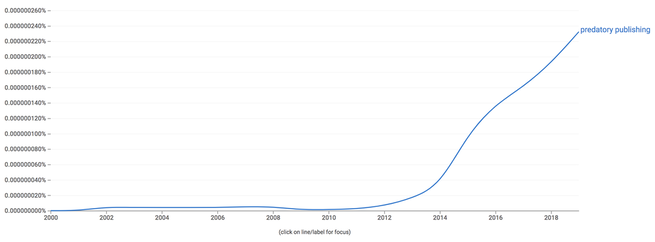

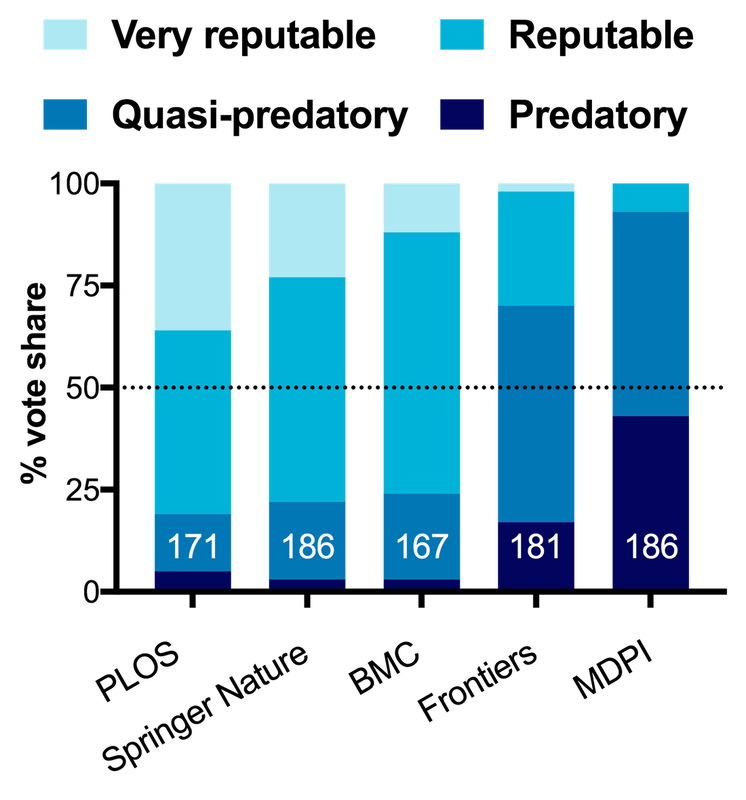

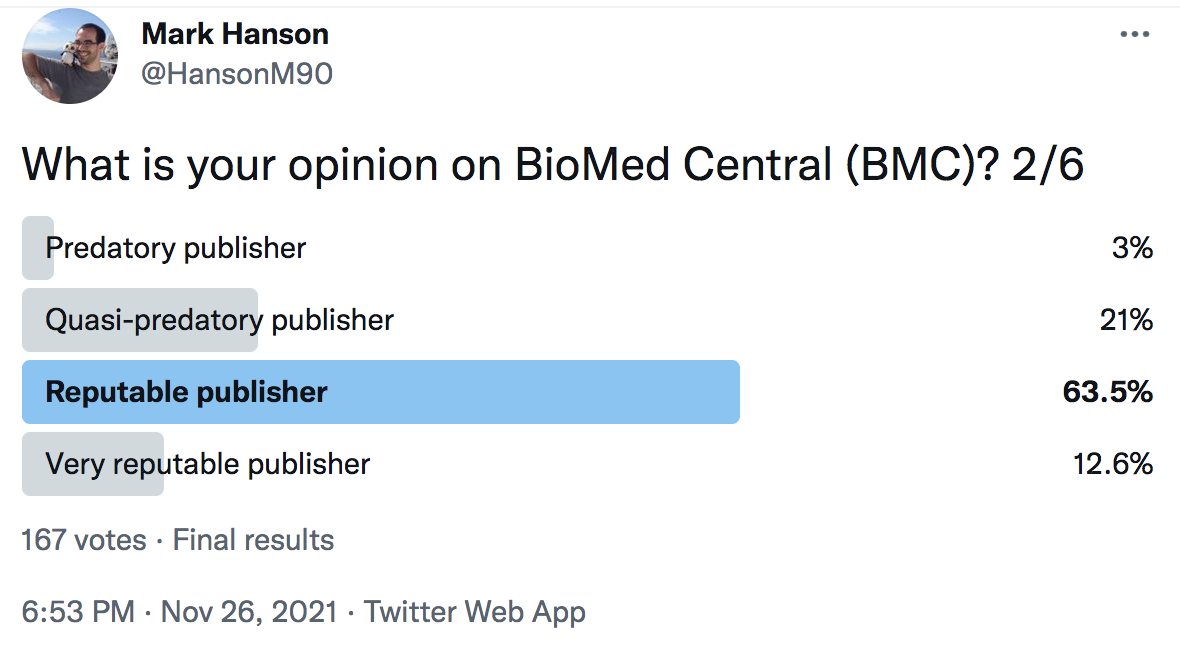

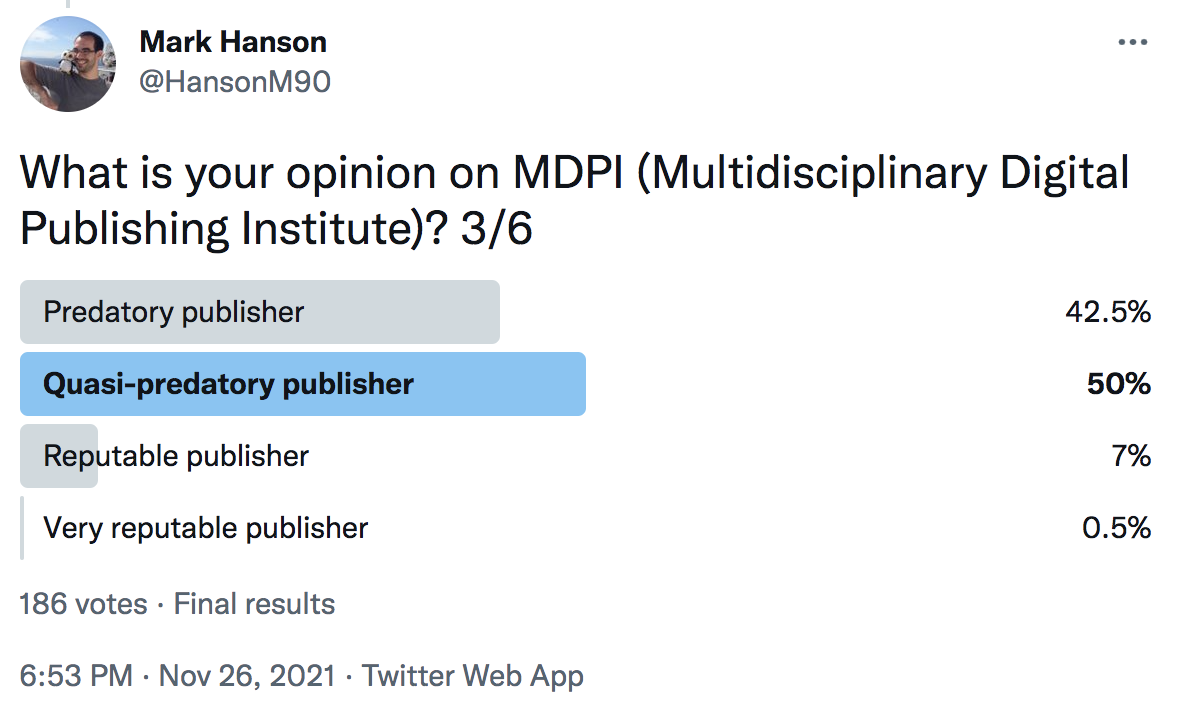

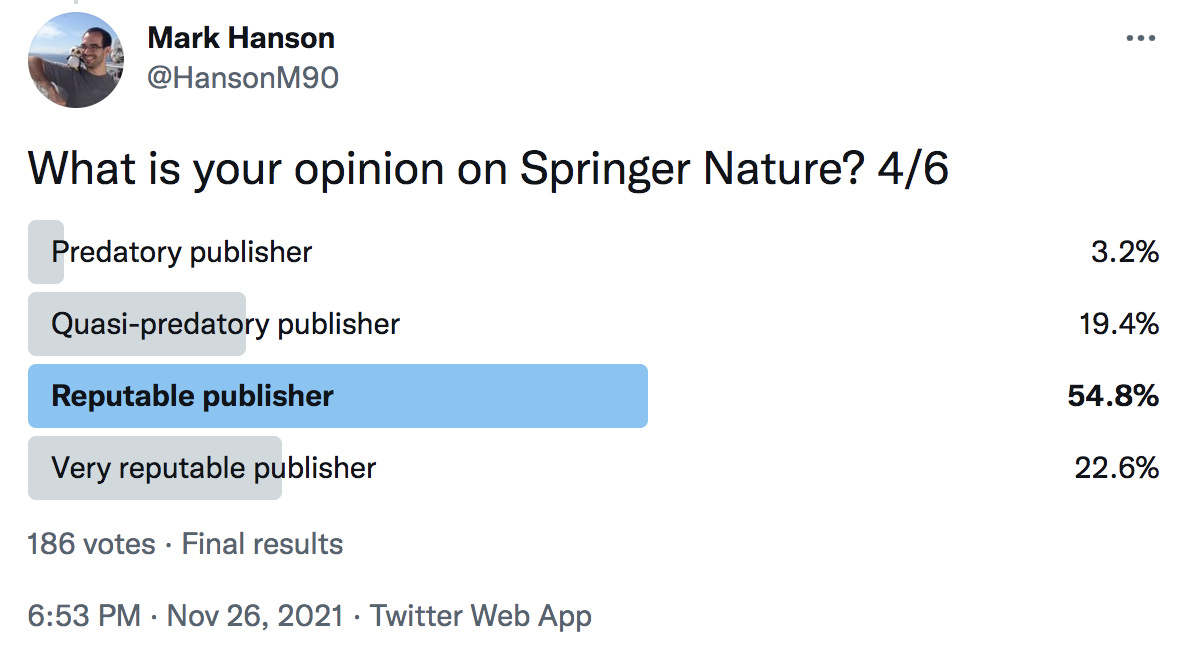

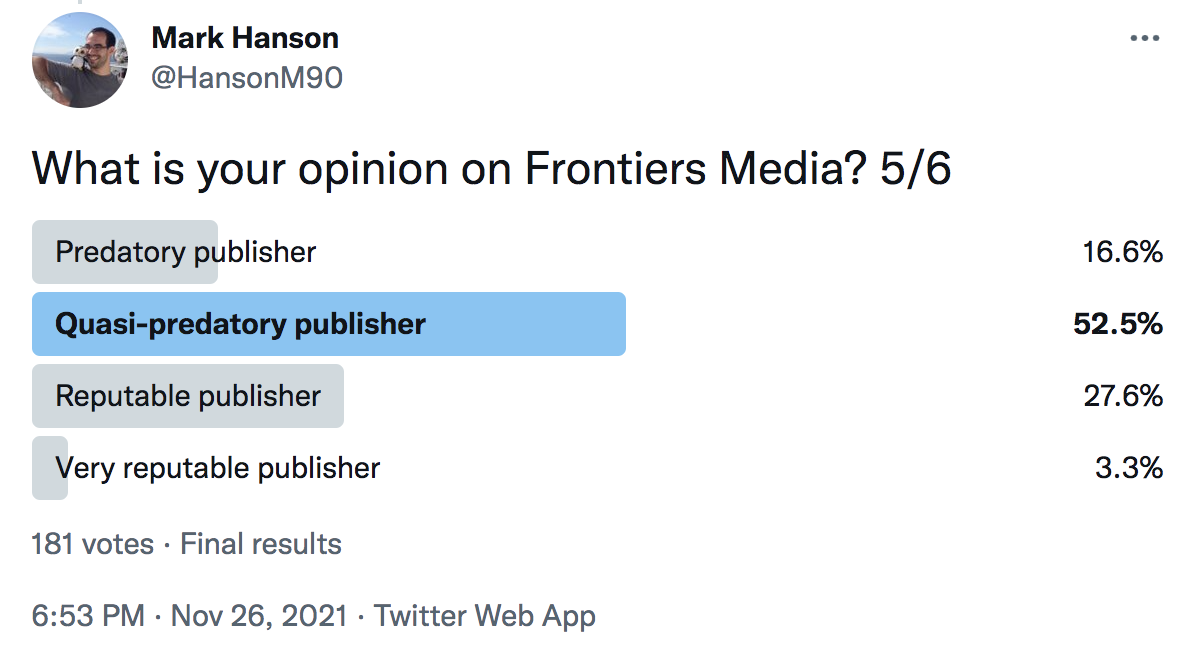

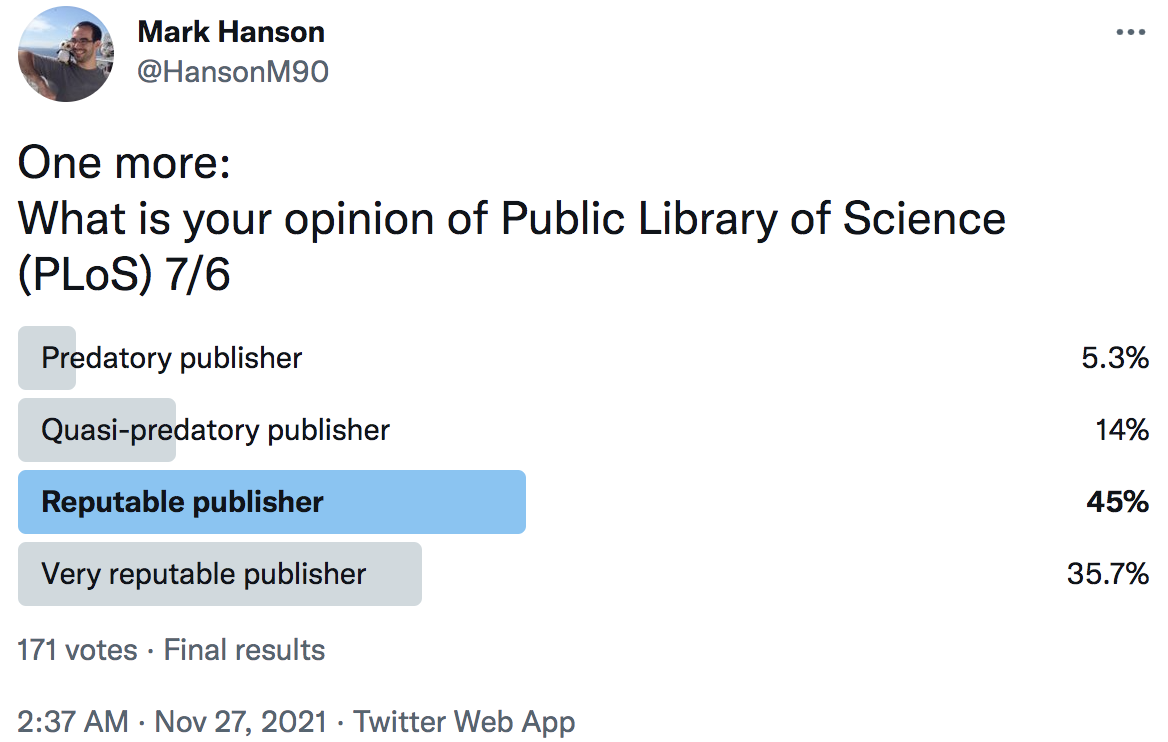

Reading time: 15 minutes You've no doubt heard the phrase "predatory publishing." The term was popularized by librarian Jeffrey Beall for his observation of "publishers that are ready to publish any article for payment" [1]. The term accurately describes the least professional publishing companies that typically do not get indexed by major publisher metrics analysts like Clarivate or Scopus. However the advent and explosive success of major Open-Access publishing companies like MDPI, Frontiers, or BMC, has led to murky interpretations of the term "predatory publishing." Some might even adopt the term to describe the exorbitant open-access prices of major journals like Nature or Science Advances [2]. A recent commentary by Paolo Crossetto [3] made the point to say that some of the strategies employed by the controversial publisher MDPI might better be referred to as "aggressive rent extracting" rather than predatory behaviour; the term is borrowed from economics, and refers to lawmakers receiving payments from interest groups in return for favourable legislation [4]. Crossetto added the caveat that their methods might lean towards more predatory behaviour over time [3]. But there's that word again: "predatory." What exactly does it mean to lean towards predatory behaviour? When does one cross the line from engaging in predatory behaviour to becoming a predatory publisher? Is predation really even the right analogy? I'll take some time to discuss the term "predatory publishing" here to try and hammer out what it means and what it doesn't mean in the modern era. The TL;DR summary is: the standards for predatory publishing have shifted, and so have the publishers. But there is a general idea out there of what constitutes predatory publishing. I make an effort to define the factors leading to those impressions, and describe some tools that the layman can use to inform themselves on predatory publishing behaviour. The original meaning of the term "predatory publishing"It's been only ~10 years since the phrase "predatory publishing" entered the lexicon. At its inception, the target group for the term was intuitive to understand. Predatory publishers had unprofessional websites, frequent spelling and grammar issues, poor editing services, and of course, a sham peer review process (at best). Some even posed as legitimate journals by registering names similar to real journals, hoping to dupe researchers into paying them article processing charges without ever publishing their papers. In 2012 Jeffrey Beall published a commentary on how the burgeoning field of open access publishing was being corrupted by such predatory publishers, and said "scholars must resist the temptation to publish quickly and easily" [1]. The crux of predatory publishingTherein lies the crux of the predatory publishing model: quick and easy publications. It is worth noting that, in and of itself, quick and easy publishing sounds like an ideal scenario rather than a threat to the integrity of science. Publishing good work should be quick and easy. The issue with this ideal is that it is in direct conflict with rigorous peer review. Quick publication increases the publisher's turnaround time, begetting even more articles to be published quickly. As Dan Brockington points out in his recent commentary [6]: "A vast increase in papers makes more mistakes more likely, especially as their scrutiny and revision gets faster. Haste may not necessarily lead to mistakes, but it makes them more likely." - Dan Brockington Therein lies the conflict. It is simply easier to get publications accepted if scientists are not spending as much time considering their merits. It's the age-old quandary of quantity vs. quality. However science is not interested in quantity without quality. The very foundation of scientific research is built on rigorous quality control: the peer review system. Haste undermines the utility of peer review. But going back to the term at hand: does that make hasty publishers predatory? What does "predatory publishing" mean in 2021?As mentioned earlier, the nature of what constituted predatory publishing was easier at the inception of the term. But in the modern day, "predatory publishing" has been co-opted to describe a range of activities including lack of rigorous peer review to exploitative publishing models. To emphasize this point, I recently conducted a Twitter poll asking participants to give their impression of five publishers: BioMed Central (BMC), Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute (MDPI), Springer Nature, Frontiers Media, and Public Library of Science (PLOS). The question and choice of answers was the same for each publisher: "What is your opinion on [insert publisher here]?" with the responses: i) predatory publisher, ii) quasi-predatory publisher, iii) reputable publisher, iv) very reputable publisher. The results are shown below. While Twitter is by no means an ideal sampling method, there is clearly a diversity of opinions on the extent of predatory practice by the publishing groups included in the polls. I was surprised to see ~1/5 votes suggesting PLOS was a predatory/quasi-predatory publisher given that PLOS is a non-profit organization... but imagine this sentiment comes from the quantity and quality of articles in its mega journal PLOS One. Nevertheless a vast majority of voters said PLOS was reputable/very reputable (>80%). On the other hand, MDPI was the polar opposite, with >90% labelling them as predatory/quasi-predatory. While some people might be a bit liberal with the label "predatory publisher," there is absolutely a distinction to be made between the reputation of a not-for-profit group like PLOS and a for-profit aggressive rent extractor like MDPI. It is noteworthy that each publishing group is in fact a member of COPE: the Committee On Publication Ethics [7] - at least at the time of writing. In my mind, this exposes a disconnect between what COPE accepts as publication ethics standard and what the community views as predatory practice. While Beall's early definition identified the motivations of predatory publishing [1], it is extremely subjective to pin down what publications are inappropriately quick and easy. A modern definition of predatory publishingThe term "predatory publisher" seems to have taken on a different meaning in the modern era. At its inception, predatory publishers were largely identifiable as the "Nigerian princes" of academic publishing (see link for context). But as emphasized in my recent Twitter poll (and others: here and here), there is a clear difference in people's perceptions of who is and is not engaging in predatory behaviour. Taking the results of such public comments in mind, it seems like the term is now more of a commentary on the publisher's article quality, ethics, and nature of their business model. With this in mind, I'll take a stab at defining red flags of the modern "predatory publisher", emboldened by the consensus amongst the polls. 1) A history of controversy over rigour of peer review. Any publisher is liable to let junk science slip through from time to time. But it is the frequency and topic of the junk content that is telling of peer review rigour. For instance, the Betham Science journal Open Chemical Physics published an article espousing a 9/11 conspiracy theory, which they subsequently deleted entirely rather than simply retract (web archive: here). Bentham Science is no longer indexed by Clarivate, Scopus, etc... The MDPI journal Vaccines recently published an anti-vaccine piece that cherry-picked data to suggest Covid vaccines were somehow harming more people than the deadly virus itself; this article was ultimately retracted [8], amongst a history of questionable articles. In 2015 Frontiers Media fired its entire editorial board behind Frontiers in Medicine and Frontiers in Cardiovascular Medicine for pushing to increase editorial independence and control over peer review [9]. However it is difficult to quantify the frequency of controversial articles, and the biases of a vocal minority could paint an unjust picture. It's difficult to really know if publishers have a disproportionate history of controversy. 2) Rapid and homogenous article processing times. This is an astute observation by Crossetto [3] that indicates a major coordinated effort across a publisher's journals. It is expected that different fields of study will have different challenges to answering reviews. For instance, requests for new experiments in nematodes can be addressed in weeks thanks to their short generation time, whereas new experiments in mice take months. It's also completely normal that some articles are good and get accepted rapidly, while others go through multiple revisions to address the flaws in the study. Heterogeneity in processing time is a sign of peer review performing its duty. The publishing group MDPI makes for a striking example of how editorial practice can override this, as they drastically restructured between 2016 and 2020, and accordingly saw an incredible shift from heterogenic article processing times to literally all journals fitting basically the same bell curve. Any publisher advertising rapid article processing as part of a "hard sell" is a red flag that their peer review process may be less rigorous (for reasons explained above).  Between 2016 and 2020, MDPI launched a massive and coordinated effort to homogenize article processing time. "Turnaround time across top journals is about 35 days from submission to acceptance, including revisions. The fact that revisions are included makes the result even more striking.[3]" "And this despite the fact that given the Special Issue model, the vast majority of papers are edited by a heterogeneous set of hundreds of different guest editors, which should increase heterogeneity." This figure is taken directly from Crossetto's blog post in Reference [3] 3) Frequent email spam to submit papers to special editions or invitations to be an editor. This one is a bit more self-explanatory. Publishers that constantly solicit articles from academics do so to make money from publishing fees. Academics frequently get invitations to special issues on topics they have only limited or no expertise in. The principle of the system works by reaching out to those looking for a quick outlet for their research, or on the principle of "a broken clock is right twice a day" by randomly targeting a researcher with a genuinely relevant special issue topic. 4) Low diversity of journals citing the publisher. This point requires nuance. If a publisher is constantly putting out low quality work that does not meaningfully contribute to the pool of scientific knowledge, its articles are unlikely to get cited by researchers publishing in other journals. This is distinct from a concept like Impact Factor, which measures only total citations, and not where those citations come from. Alternate journal rank metrics like SCImago Journal Rank (SJR [10]) have an internal control that penalizes journals for being cited by only a low diversity of other journals. Thus SJR is a metric one can use to get a different rank perspective on a publisher compared to the Impact Factor (more below). 5) High rates of within network citation / self-citation. The rate of self-citation is also intrinsically tied to the diversity of citing journals, but the two are distinct sides of the same coin. Simply because research is low quality does not mean the authors are forced to excessively cite themselves or other journals within the publisher's network. The practice of self-citation artificially and problematically inflates an individual's h-index or a journal's Impact Factor. Both are tools used by institutions to judge a candidate's productivity, making abuse of the system attractive. In more nefarious circles, coordination amongst a group of journals can cause editorial oversight that increases within-network citation count, a practice that has been referred to as "citation cartels" [11]. It is however difficult to assess whether high rates of within-network citation amongst journals are because of coordinated abuse by the publisher, or if instead the publisher has attracted a disproportionately high number of submissions from authors that excessively self-cite. In either scenario, the publisher is responsible for the work being published, and it speaks to a lack of editorial standards. How to spot a modern predatory publisherIndividually, any of the above red flags is not sufficient to address whether a publisher is truly "predatory." However should a publisher be engaging in all of the practices above, I think there is a strong case to be made that the publisher fits the modern definition of predatory publishing practice. So how can one safeguard against contributing time and effort towards lining the pockets of predatory publishers? Spotting Red flag #1 is relatively easy. Wikipedia articles often have lists of controversial articles for publishers with a reputation for controversies (e.g. see the Wiki articles for Frontiers Media, MDPI, Bentham Science, or OMICS Publishing Group). More reputable publishers do not earn this distinction (see e.g. BioMed Central or PLOS). A quick google search of "[Publisher Name] controversy" can also give a very rapid sense of how often a publisher is making headlines, and for what reasons. For instance Springer Nature has a more complicated history with Chinese influence, particularly involving censorship of articles mentioning Taiwan. But Springer Nature has relatively few major controversies over rigour of peer review (but see [12]). Spotting Red flags #2 and #3 are less intuitive. Unless a publisher is explicitly advertising rapid article processing times by email spam, getting this info can be difficult. Again, in and of itself rapid article processing is not proof of predatory publishing. But it is consistent with and perhaps even begets predatory publishing behaviour. Likewise, an invitation to submit an article might be welcome the first time, but should you receive numerous invitations to various special issues (of questionable relevance to your expertise), this should be a red flag. I actually have a technique to help spot Red flags #4 and #5. The technique uses publicly available data to assess a publisher's self-citation tendency. To illustrate how this example works, I have taken a recent figure put out by MDPI that they used to comment on their own rates of MDPI network self-citation practice. They seem to think comparing their rates of self-citation per article published paints them in a positive/neutral light. Their figure (with light annotation by myself) is provided below.  The following graph comes from MDPI's defence [13] of its self-citation practices highlighted in [14]. MDPI argued: "It can be seen that MDPI is in-line with other publishers, and that its self-citation index is lower than that of many others; on the other hand, its self-citation index is higher than some others." Yet it is abundantly clear that MDPI (blue) is a major outlier in every respect. It has no peers with similar total publications that even come close to approaching its level of self-citation. MDPI is also amongst the highest self-citing publishers in the entire pool (by my count in the top 10 percentile), which bizarrely included a Ukranian government fisheries journal that cites its own annual reports, and groups with extremely niche interest like the AIAA. Importantly, the analysis provided by MDPI of their own citation metrics is a striking incongruence between the data and their interpretation. MDPI appears to have put forth a public statement admitting that it believes its current self-citation practices are normal and standard, despite presenting all evidence to the contrary. MDPI is a clear outlier for self-citations given its number of publications, even in their own curated list of publishers. There is also a clear linear trend amongst the mega publishers that shows more publications begets more self-citations. This is somewhat intuitive: the more total publications you produce, the more publications you have to cite, and the more likely it is that your articles will cite a publication within your network. Yet MDPI drastically departs from this linear relationship. This result actually validates an earlier analysis I ran on publisher citation metrics back in August (see blog post here). I was trying to find a way to infer self-citation rates with publicly available data. In that analysis, I used the ratio of Impact Factor and SCImago Journal Rank (IF/SJR) to reveal publishers with disproportionately low diversity of journals citing their work (Red Flag #4) and/or disproportionately high Impact Factors caused by excessive self-citation (Red Flag #5). I called this the level of "Impact Factor Inflation" by publishing groups. The key finding is below:  Distribution of Impact Factor (IF) / SCImago Journal Rank (SJR). A higher IF/SJR indicates "Impact Factor Inflation" by a given publisher. It is clear that Not-for-profit publishers ("NFP," including society journals, Public Library of Science, and Company of Biologists) do not have nearly the same IF/SJR ratios as open access mega publishers (p<.05 across the board). My analysis also found that the IF/SJR distributions of BMC and Frontiers were only marginally different (p < .10), but in all cases MDPI had significantly higher IF/SJR than any other publishing group (p < e-7). This Impact Factor Inflation ratio (IF/SJR) very neatly delineates reputable not-for-profit publishers from open-access mega publishers, and most especially from MDPI. While not shown here, MDPI also was not significantly different from a control predatory publisher "Bentham Science." My conclusion from the analysis was that MDPI had an IF/SJR akin to a predatory publisher. I therefore suggested that an IF/SJR > 4.0 (the lower quartile of MDPI variance) might be indicative of predatory publishing behaviour. The IF/SJR metric is a rapid way to gain some insight on a publisher's practices, and especially useful to the layman as both data values are publicly available through SCImago directly. Up-to-date Impact Factors are also typically advertised on journal websites. Closing thoughtsThe apparent consensus within the Twitter scientific community is that practices by publishers like MDPI overwhelmingly deserve the label "predatory/quasi-predatory." A publisher like Frontiers Media on the other hand is straddling the line, where only a small minority (~17%) are willing to outright call them predatory, and a reasonable chunk of respondents (~31%) still think of them as reputable/very reputable. I think any publisher engaging in all five of the red flag practices I've described - to me - meets the modern definition of predatory publisher. It's extremely difficult to quantify red flags #1, #2, and #3, but certainly word gets around. The IF/SJR "Impact Factor Inflation" ratio I've defined further provides insight on red flags #4 and #5. There's also a clear correlation between IF/SJR and the Twitter polling, suggesting IF/SJR is a good proxy for general impressions. So what is a predatory publisher anyways? Despite an evolving landscape, I think the stigma attached to the word remains useful. While this blanket label glosses over a lot of nuance, it is an effective form of communicating the message to a broad audience that a publisher is engaging in poor practices. In my red flags, I've tried to capture the defining sentiments behind what makes a publisher "predatory" in the modern era. There is undoubtedly a liberal use of the term that does not rely on a publisher being recognized by COPE or indexed by metrics companies like Clarivate. But the scientific community clearly has their own opinion; and the data seem to support it. References:

Ulrich G. Hofmann

12/10/2021 04:20:33 am

Any idea how the Springer-Nature distribution or the Elsevier distribution would fit into your graph on Impact Factor Inflation? The one I checked made the impression similar to BMS's ...

Mark

12/11/2021 12:57:52 am

Unfortunately I don't have access to a systematic database. I had to compile the MDPI, Frontiers, BMC etc... IFs and SJRs manually. So I simply can't pull out whole-publisher data on the likes of Springer or Elsevier; not enough hours in the day. Comments are closed.

|

AuthorMark Archives

July 2024

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed