|

Reading time: 13 minutes

TLDR: "Think piece" and "Frankenstein" Special Issues are very different things. We should really be distinguishing them from each other. It's publishers that profit off of free guest editor work that want us to view all things called "Special Issues" as similar products. They aren't, and we need terms that define a spectrum for what goes into editing a "Special Issue."

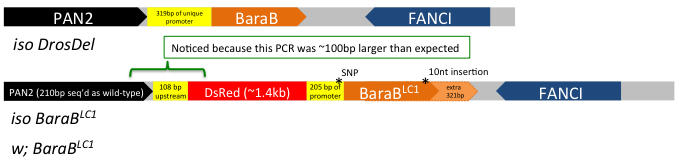

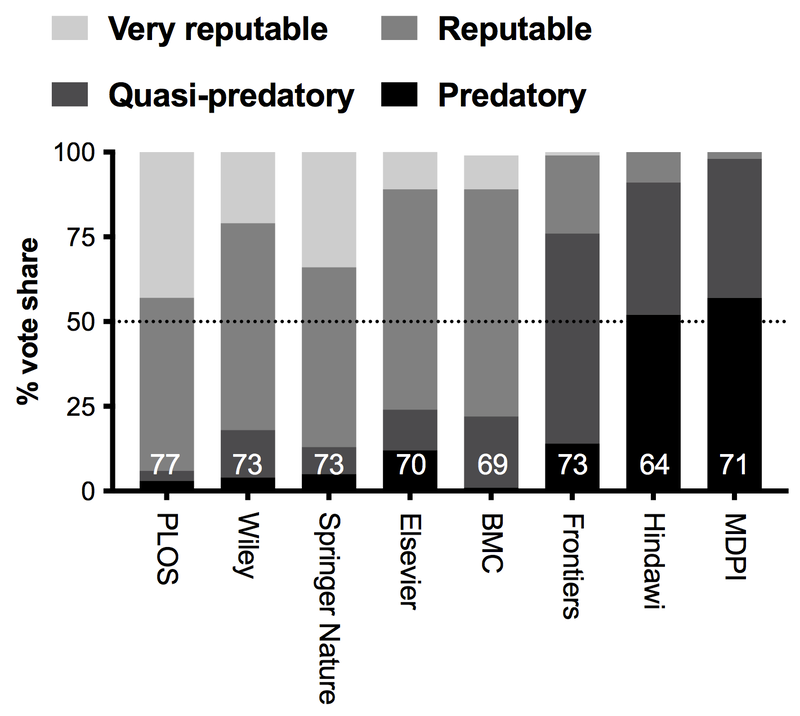

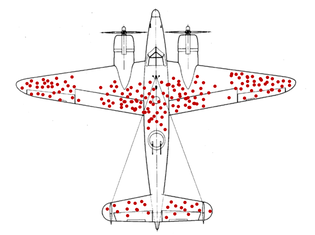

Figure: Special Issue (red) and Regular Issue (blue) articles by publisher from The strain on scientific publishing.

So you may have read a preprint recently: "The strain on scientific publishing." I found the topic fascinating; heck, I was lead author. In that preprint, we highlighted two mechanisms of publisher growth that generates strain, one of which was the use of "Special Issues" (emphasis on the air quotes). Some publishers have adopted Special Issues as an outlet for publishing guest-edited articles en masse. Now, our preprint took off across the globe, being covered in English, Spanish, Arabic, and Swahili... just to name a few. Somewhat as a result, we've even been attacked by Frontiers Media for somehow being "anti-special issue," which is the topic of today's post: am I anti-special issue? I don't think so. After all, I just finished editing one.

What is a journal?

|

| I was far from the first to highlight MDPI's poor reputation. Dan Brockington held a questionnaire series asking affiliates of MDPI (authors, reviewers, editors) on their opinion of the publisher in ~2020. I particularly love one of his simple summaries of the heart of the issue regarding MDPI's publishing behaviour: "Haste may not necessarily lead to mistakes, but it makes them more likely." |

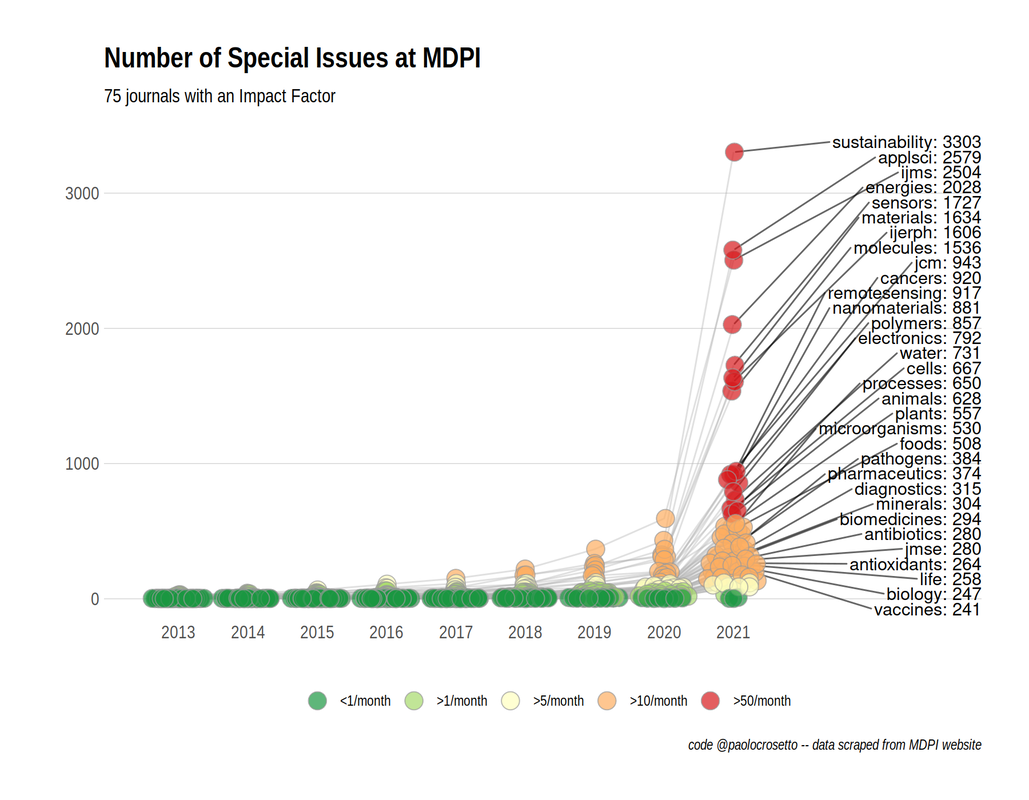

Around the same time, Paolo Crosetto wrote a fantastic piece on MDPI's anomolous growth of Special Issues. Year-after-year growth of Special Issues exploded between 2020 and 2021, going from 6,756 in 2020 to 39,587 in 2021. The journal Sustainability has been publishing ~10 special issues per day: and keep in mind a special issue is often comprised of ~10 articles. As Crosetto put it: "If each special issue plans to host six to 10 papers, this is 60 to 100 papers per day. At some point, you are bound to touch a limit – there possibly aren’t that many papers around... That’s not to talk about quality, because even if you manage to attract 60 papers a day, how good can they be?”

| At some point, you are bound to touch a limit – there possibly aren’t that many papers around. - Paolo Crosetto | This really resonated with me, particularly as someone who is currently hosting a special issue with a different (society journal) publisher. Special Issues are supposed to be special; it's easy to forget that sometimes, but it's actually very important! |

Not-so-special issues

Reading time: 10-12 minutes

In this article:

Edit Mar 25th 2023: moved Twitter vs. Mastodon tangent to "p.s." section

In this article:

- "Predatory publishing" is an overly-vague term

- Poll 2023: What is a predatory publisher anyways?

- Moving past the word "predatory"

- Vampire press (similar to "vanity press")

- Rent-seeker / Rent-extractor

- Scam

Edit Mar 25th 2023: moved Twitter vs. Mastodon tangent to "p.s." section

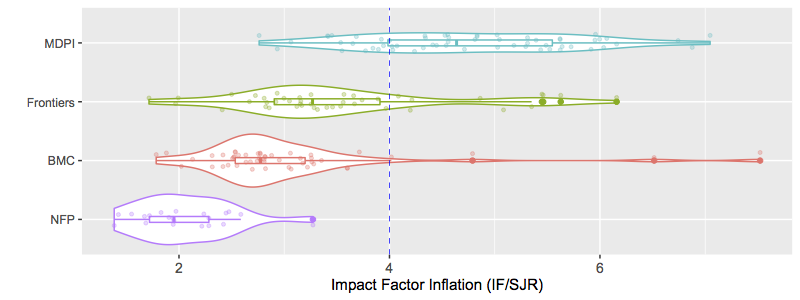

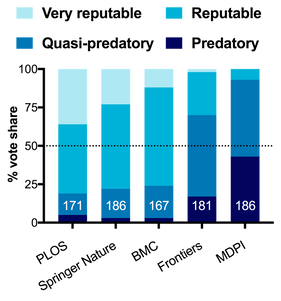

A year ago I wrote a blogpost called "What is a predatory publisher anyways?" In that post I looked at the origin of the term in 2012, and what it meant at its inception. I held a Twitter poll, gathering ~175 respondents from across the spectrum that asked people's opinions on whether various publishing groups were "predatory."

SPOILERS: I just redid the poll in Jan 2023 on both Twitter and Mastodon.

The aim of that poll was not only to get a sense of publisher reputations, but to look at what are the behaviours of publishers that people associate with "predatory publishing." What did I learn in 2021? Well... not exactly what I expected (fun!).

SPOILERS: I just redid the poll in Jan 2023 on both Twitter and Mastodon.

The aim of that poll was not only to get a sense of publisher reputations, but to look at what are the behaviours of publishers that people associate with "predatory publishing." What did I learn in 2021? Well... not exactly what I expected (fun!).

"Predatory publishing" is an overly-vague term

Reading time: 6-8 minutes

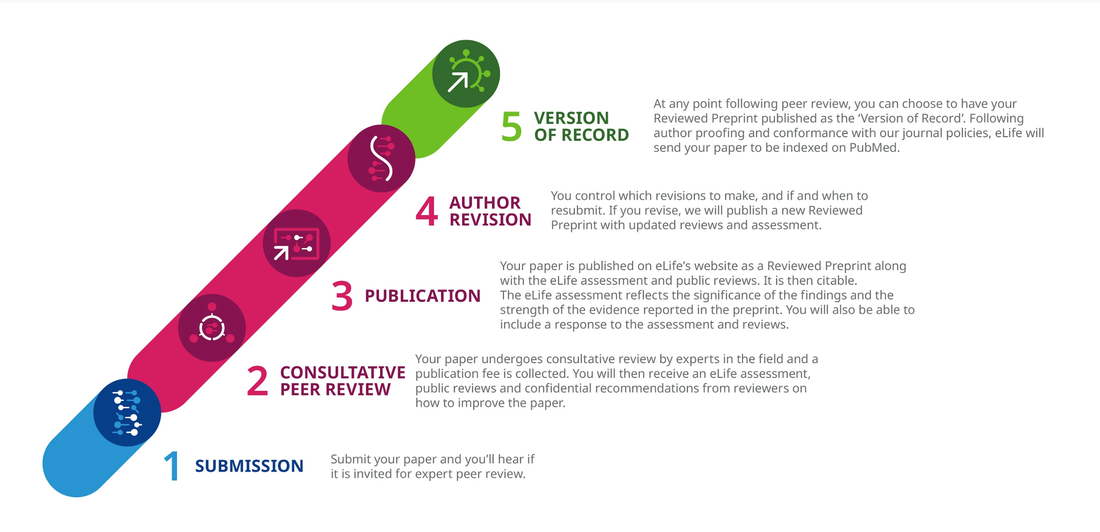

The announcement by eLife to do away with formal accept/reject decisions has caused quite a stir. One of the major claims of the eLife announcement was:

“By relinquishing the traditional journal role of gatekeeper and focusing instead on producing public peer reviews and assessments, eLife is restoring control of publishing to authors, recovering the immense value that is lost when peer reviews are reduced to binary publishing decisions, and promoting the evaluation of scientists based on what, rather than where, they publish.”

I've underlined a couple key points in that statement. If you haven't already, I'd recommend reading my 5 minute take on the eLife announcement for full context. But I'll just dissect these two points here:

1. "eLife is restoring control of publishing to authors"

"Restoring" is a weird word isn't it? Since when have authors had control over publishing? I would argue that, even in the era before modern peer review (pre-1970ish) authors still didn't have control over where they published. In my last article, I made a point about how this is, in part, because experts need to be accountable to other experts (authors, reviewers, or editors). But even ignoring that, strictly from a marketing standpoint, there's no point in human history where an author could effectively disseminate their work - fiction, academic, or other - without the aid of a publishing house. Darwin didn't print, bind, and distribute all his own copies of "On the Origin of Species" any more than Harper Lee ran the printing press to produce every copy of "To Kill a Mockingbird." And neither of them saw to all the intricacies of marketing their work, distributing it, or filling orders.

"But we're in the internet age. We have social media for dissemination and we can even use LaTEX or rely on algorithms (e.g. bioRxiv web versions) to typeset our work." That's true. It's a fair point. But social media is only really effective if you start with a following. There are tons of stupid cat videos on the internet, but the ones you're most likely to see are coming from just a few famous channels. Don't forget survivor bias: for all the social media success stories out there, there are tens of thousands that completely failed. And the ones that succeeded are often propped up by shout-outs from existing prominent users. Take it from me, fun fact: I used to run a skateboarding trick tips YouTube channel back from 2007-2011: the early days of YouTube. I was even successful enough that my "How To Ollie" video came up before Tony Hawk's. But I was only successful because I produced videos that were half-decent at a time when YouTube was devoid of content. Were I to start my channel today, I'd be lucky to reach even a level of fame best described as "obscure."

So why do scientists think disseminating their work by social media is any different? Why do scientists think that they can start a Twitter, reddit, Facebook, post a link to their few hundred followers and "boom!" their work is out in the world! Sure, some preprints take off like wildfire. But that brings me to my second point...

The announcement by eLife to do away with formal accept/reject decisions has caused quite a stir. One of the major claims of the eLife announcement was:

“By relinquishing the traditional journal role of gatekeeper and focusing instead on producing public peer reviews and assessments, eLife is restoring control of publishing to authors, recovering the immense value that is lost when peer reviews are reduced to binary publishing decisions, and promoting the evaluation of scientists based on what, rather than where, they publish.”

I've underlined a couple key points in that statement. If you haven't already, I'd recommend reading my 5 minute take on the eLife announcement for full context. But I'll just dissect these two points here:

1. "eLife is restoring control of publishing to authors"

"Restoring" is a weird word isn't it? Since when have authors had control over publishing? I would argue that, even in the era before modern peer review (pre-1970ish) authors still didn't have control over where they published. In my last article, I made a point about how this is, in part, because experts need to be accountable to other experts (authors, reviewers, or editors). But even ignoring that, strictly from a marketing standpoint, there's no point in human history where an author could effectively disseminate their work - fiction, academic, or other - without the aid of a publishing house. Darwin didn't print, bind, and distribute all his own copies of "On the Origin of Species" any more than Harper Lee ran the printing press to produce every copy of "To Kill a Mockingbird." And neither of them saw to all the intricacies of marketing their work, distributing it, or filling orders.

"But we're in the internet age. We have social media for dissemination and we can even use LaTEX or rely on algorithms (e.g. bioRxiv web versions) to typeset our work." That's true. It's a fair point. But social media is only really effective if you start with a following. There are tons of stupid cat videos on the internet, but the ones you're most likely to see are coming from just a few famous channels. Don't forget survivor bias: for all the social media success stories out there, there are tens of thousands that completely failed. And the ones that succeeded are often propped up by shout-outs from existing prominent users. Take it from me, fun fact: I used to run a skateboarding trick tips YouTube channel back from 2007-2011: the early days of YouTube. I was even successful enough that my "How To Ollie" video came up before Tony Hawk's. But I was only successful because I produced videos that were half-decent at a time when YouTube was devoid of content. Were I to start my channel today, I'd be lucky to reach even a level of fame best described as "obscure."

So why do scientists think disseminating their work by social media is any different? Why do scientists think that they can start a Twitter, reddit, Facebook, post a link to their few hundred followers and "boom!" their work is out in the world! Sure, some preprints take off like wildfire. But that brings me to my second point...

Reading time: 5 minutes

For another perspective focused more on the issue of asking readers to do even more to navigate the "fire hose of information" spewing at them: a good piece by Stephen Heard

Let me start by saying: the new eLife model is bold, and I am a big fan of eLife. I do not think it will be the end of the journal. I don't think it should even tarnish eLife's reputation much. In fact, I think I like it. But that's because, as far as I can tell, eLife has simply traded "hard" power for "soft" power in editorial decisions.

Now I do have a concern with the very direction eLife is heading: I think it's bad for the health of science. I think it's a push towards the death of expertise. Contrary to many, I like journals. I even like journals I hate. I like them because they're expert authorities, and the world needs expert authorities. This isn't about the pursuit of an idyllic science publishing landscape, it's about the nature of science communication to human beings, which last I checked, describes me aptly. It's about how we maintain accountability over information flow, over scientific rigour. I like the eLife proposal precisely because eLife has... in reality... hardly done anything. But all the pomp in the announcement they've made is a direction I do not want to see science go, and one I think is genuinely dangerous.

With that said...

So I hear eLife announced a thing?

Yes, yes dear reader they did. Here's some important context before we get into the announcement (from: link):

So what did eLife announce? Here's the jist (from: link):

Two comments:

Point #1: Effectively, editors now have the power to desk-accept papers before they're even sent for review. Just think about that as we continue re: gatekeeping.

Point #3: I have not seen near enough acknowledgement of this in the public discourse. The fact that there's an editor statement within the article itself means that regardless of whether one reads the reviews (99% won't), there is an up-front assessment of the work attached.

For another perspective focused more on the issue of asking readers to do even more to navigate the "fire hose of information" spewing at them: a good piece by Stephen Heard

Let me start by saying: the new eLife model is bold, and I am a big fan of eLife. I do not think it will be the end of the journal. I don't think it should even tarnish eLife's reputation much. In fact, I think I like it. But that's because, as far as I can tell, eLife has simply traded "hard" power for "soft" power in editorial decisions.

Now I do have a concern with the very direction eLife is heading: I think it's bad for the health of science. I think it's a push towards the death of expertise. Contrary to many, I like journals. I even like journals I hate. I like them because they're expert authorities, and the world needs expert authorities. This isn't about the pursuit of an idyllic science publishing landscape, it's about the nature of science communication to human beings, which last I checked, describes me aptly. It's about how we maintain accountability over information flow, over scientific rigour. I like the eLife proposal precisely because eLife has... in reality... hardly done anything. But all the pomp in the announcement they've made is a direction I do not want to see science go, and one I think is genuinely dangerous.

With that said...

So I hear eLife announced a thing?

Yes, yes dear reader they did. Here's some important context before we get into the announcement (from: link):

- eLife desk rejects about 70% of manuscripts they receive.

- Of the 30% of manuscripts they send for review, they accept about half (16% of overall submissions are ultimately accepted).

- eLife (and Review Commons, which eLife is a member of) has a unique style of peer review that I LOVE. Reviewers submit their reviews, but before they're sent to the author, reviewers also chat with each other briefly and come to a consensus. The final product is reviews where reviewers can reflect on their critiques before they're submitted to authors. Brilliant move to reign in biased reviews.

So what did eLife announce? Here's the jist (from: link):

- eLife will no longer stamp an "accept/reject" on a paper any more. Instead, regardless of review outlook, they will let the author choose when the paper is published as its version of record (indexed in PuBmed etc...).

- eLife will publish the paper as a peer-reviewed preprint, with the reviews and the author response on the eLife website.

- The editor will write a significance statement to be attached at the head of the article.

Two comments:

Point #1: Effectively, editors now have the power to desk-accept papers before they're even sent for review. Just think about that as we continue re: gatekeeping.

Point #3: I have not seen near enough acknowledgement of this in the public discourse. The fact that there's an editor statement within the article itself means that regardless of whether one reads the reviews (99% won't), there is an up-front assessment of the work attached.

Reading time: 5 minutes

TL;DR: we need to talk about predatory publishing publicly. This means defining 'control' publishers that are definitely predatory. Only then can we have a meaningful conversation about where more ambiguous controversial publishers sit on the spectrum.

Silence equals consent - qui tacet consentire videtur

Let me start with a thesis statement:

"The most significant issue around predatory publishing today is the fact that no one is talking about it."

At this point, I think most scientists have heard of 'predatory publishing' (if you haven't, read this). But I would say very few can actually name a predatory publishing group, particularly if the verdict has to be unanimous. To be honest, I only know of a couple famous examples of unambiguously 'predatory' publishing groups: Bentham Science Publishers and OMICS publishing group. It seems like we all have a sense of what a predatory publisher is. However the term is so poorly defined in the public consciousness that actually identifying a journal/publisher as "predatory" is extremely difficult. It is a conversation we are not used to having, which makes it very hard to use this label for anything.

There are numerous reasons for this:

There are numerous reasons for this:

Reading time 10 min

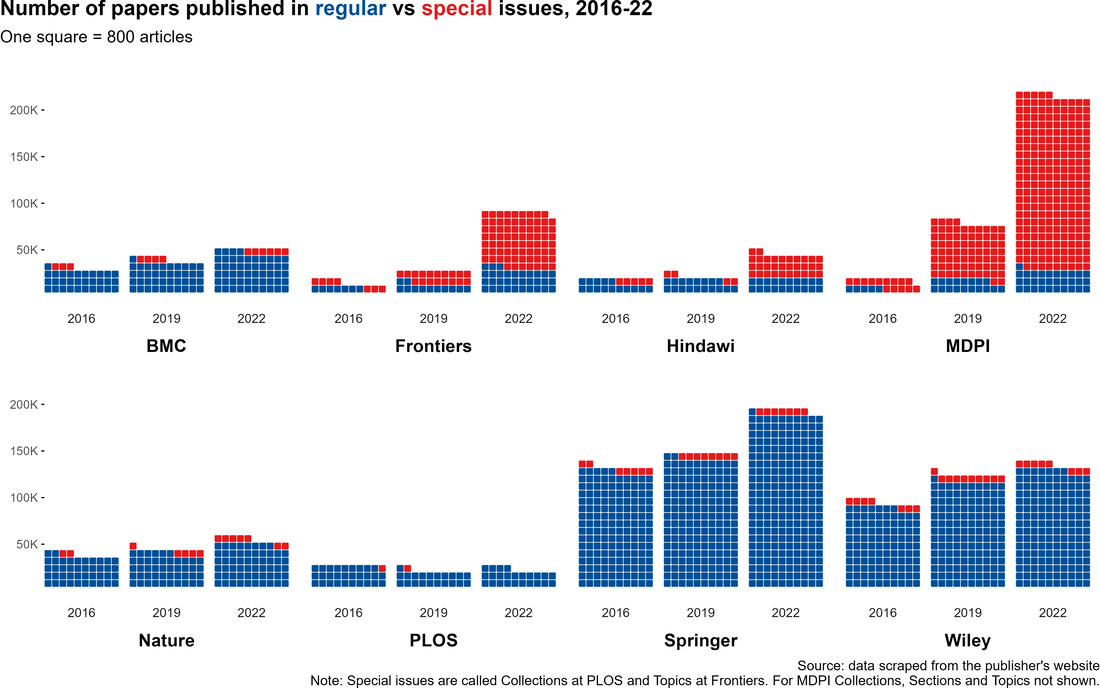

TL;DR: I re-ran the IF/SJR analysis focused on publishers highlighted by MDPI as contemporaries with very high self-citation rate. Many of those publishing groups included non-profit professional societies. Like other non-profits, their IF/SJR were very low and drastically different from MDPI. This also brought IGI Global into the mix, which has been referred to as a "vanity press" publisher that contributes little beyond pumping up people's CVs with obscure academic book chapters. IGI Global and my control predatory publisher (Bentham) were the only groups with an IF/SJR comparable to MDPI.

I recently shared some thoughts on what defines a modern predatory publisher. In that post (see here [1]), I defined five red flags that act as markers of predatory behaviour. These were: #1) a history of controversy over rigour of peer review, #2) rapid and homogenous article processing times, #3) Frequent email spam to submit papers to special editions or invitations to be an editor, #4) low diversity of journals citing works by a publisher, and #5) high rates of self-citation within a publisher's journal network.

Overall, the post seems to have been well-received (I like to think!). One tool I proposed to help spot predatory publishing behaviour was to use the difference in how Impact Factor (IF) and Scimago Journal Rank (SJR) metrics were calculated to expose publishers with either: #4) low diversity of journals citing works by a publisher and/or #5) high rates of self-citation within a publisher's journal network. I'll reiterate that one should really judge all five red flags in making conclusions about a publisher, but today I'll focus on the IF/SJR metric.

TL;DR: I re-ran the IF/SJR analysis focused on publishers highlighted by MDPI as contemporaries with very high self-citation rate. Many of those publishing groups included non-profit professional societies. Like other non-profits, their IF/SJR were very low and drastically different from MDPI. This also brought IGI Global into the mix, which has been referred to as a "vanity press" publisher that contributes little beyond pumping up people's CVs with obscure academic book chapters. IGI Global and my control predatory publisher (Bentham) were the only groups with an IF/SJR comparable to MDPI.

I recently shared some thoughts on what defines a modern predatory publisher. In that post (see here [1]), I defined five red flags that act as markers of predatory behaviour. These were: #1) a history of controversy over rigour of peer review, #2) rapid and homogenous article processing times, #3) Frequent email spam to submit papers to special editions or invitations to be an editor, #4) low diversity of journals citing works by a publisher, and #5) high rates of self-citation within a publisher's journal network.

Overall, the post seems to have been well-received (I like to think!). One tool I proposed to help spot predatory publishing behaviour was to use the difference in how Impact Factor (IF) and Scimago Journal Rank (SJR) metrics were calculated to expose publishers with either: #4) low diversity of journals citing works by a publisher and/or #5) high rates of self-citation within a publisher's journal network. I'll reiterate that one should really judge all five red flags in making conclusions about a publisher, but today I'll focus on the IF/SJR metric.

Reading time: 15 minutes

You've no doubt heard the phrase "predatory publishing." The term was popularized by librarian Jeffrey Beall for his observation of "publishers that are ready to publish any article for payment" [1]. The term accurately describes the least professional publishing companies that typically do not get indexed by major publisher metrics analysts like Clarivate or Scopus. However the advent and explosive success of major Open-Access publishing companies like MDPI, Frontiers, or BMC, has led to murky interpretations of the term "predatory publishing." Some might even adopt the term to describe the exorbitant open-access prices of major journals like Nature or Science Advances [2]. A recent commentary by Paolo Crossetto [3] made the point to say that some of the strategies employed by the controversial publisher MDPI might better be referred to as "aggressive rent extracting" rather than predatory behaviour; the term is borrowed from economics, and refers to lawmakers receiving payments from interest groups in return for favourable legislation [4]. Crossetto added the caveat that their methods might lean towards more predatory behaviour over time [3].

But there's that word again: "predatory." What exactly does it mean to lean towards predatory behaviour? When does one cross the line from engaging in predatory behaviour to becoming a predatory publisher? Is predation really even the right analogy?

I'll take some time to discuss the term "predatory publishing" here to try and hammer out what it means and what it doesn't mean in the modern era.

The TL;DR summary is: the standards for predatory publishing have shifted, and so have the publishers. But there is a general idea out there of what constitutes predatory publishing. I make an effort to define the factors leading to those impressions, and describe some tools that the layman can use to inform themselves on predatory publishing behaviour.

You've no doubt heard the phrase "predatory publishing." The term was popularized by librarian Jeffrey Beall for his observation of "publishers that are ready to publish any article for payment" [1]. The term accurately describes the least professional publishing companies that typically do not get indexed by major publisher metrics analysts like Clarivate or Scopus. However the advent and explosive success of major Open-Access publishing companies like MDPI, Frontiers, or BMC, has led to murky interpretations of the term "predatory publishing." Some might even adopt the term to describe the exorbitant open-access prices of major journals like Nature or Science Advances [2]. A recent commentary by Paolo Crossetto [3] made the point to say that some of the strategies employed by the controversial publisher MDPI might better be referred to as "aggressive rent extracting" rather than predatory behaviour; the term is borrowed from economics, and refers to lawmakers receiving payments from interest groups in return for favourable legislation [4]. Crossetto added the caveat that their methods might lean towards more predatory behaviour over time [3].

But there's that word again: "predatory." What exactly does it mean to lean towards predatory behaviour? When does one cross the line from engaging in predatory behaviour to becoming a predatory publisher? Is predation really even the right analogy?

I'll take some time to discuss the term "predatory publishing" here to try and hammer out what it means and what it doesn't mean in the modern era.

The TL;DR summary is: the standards for predatory publishing have shifted, and so have the publishers. But there is a general idea out there of what constitutes predatory publishing. I make an effort to define the factors leading to those impressions, and describe some tools that the layman can use to inform themselves on predatory publishing behaviour.

Summary (TL;DR)

Predatory publishing is a significant issue in scientific discourse. Predatory publishers erode the integrity of science in the public eye due to accepting poor quality work or even misinformation advertised as professional investigation, and harm scientists that contribute time and money to aid these disreputable companies. Recent conversations around the Multidisciplinary Publishing Institute (MDPI) have accused MDPI of engaging in predatory practices. Notably, MDPI journals have been observed with high self-citation rates, which artificially inflate their Impact Factor compared to honest scientific discourse. Here I use a novel metric to assess whether MDPI journals have artificially inflated their Impact Factor: the ratio of Impact Factor (IF) to SCImago Journal Rank (SJR). This IF/SJR metric readily distinguishes reputable not-for-profit publishers from a known predatory publisher (Bentham Open), and also from MDPI. I further included a spectrum of for-profit and non-profit publishing companies in the analysis, including Frontiers, BMC, and PLoS. My results inform on the degree of predatory publishing by each of these groups, and indicate IF/SJR as a simple metric for assessing a publisher's citation behaviour. I suggest that an IF/SJR ratio >4 is an indication of possible predatory behaviour, and scientists approached by publishers with IF/SJR > 4 should proceed with caution. Importantly, the IF/SJR ratio can be determined easily and without relying on data hiding behind paywalls.

Background

The full dataset and R scripts used for the analysis are provided as a .zip file at the end of this article.

Predatory publishing is a major issue in the scientific literature. Briefly: predatory publishers basically pose as legitimate scientific journals, but fail to perform the minimum rigour as curators of scientific information. Nowadays, outright fake journals are readily spotted by careful scientists, but quasi-predatory publishers can appear quite professional and are much more difficult to identify.

Quasi-predatory publishers are identifiable by a few key factors (I have selected a few factors discussed in Ref [1]):

Regarding this fourth point, a journal's Impact Factor (IF) is an important metric that is used by granting agencies and scientists to judge a journal's prestige (for better or worse). The IF is determined by the average number of citations articles get when published in that journal. Importantly, the IF number can be artificially inflated by authors citing themselves or their close colleagues in a biased fashion [2]. On the surface, this gives the impression that the scientist or journal is highly productive and well-recognized. This gives predatory publishers a significant incentive to engage in self-citation practices that inflate their Impact Factor. Predatory publishers do this by citing work from their own network of journals in an unabashedly biased fashion [1]. I'll be referring to this as "Impact Factor Inflation" hereon (see [3]).

Analyses like this one and studies like this one [1] have already discussed the quasi-predatory or even outright predatory behaviour of MDPI, which has grown more bold and problematic in recent years. The recommendation of Ref [1] was that scientific journal databases should remove MDPI due to predatory behaviour, indicating the degree of the issue being debated with MDPI. In particular, MDPI was seen to have significant self-citation issues, alongside 'citation cartels', networks of journals that cite each other to artificially inflate their impact factor [1].

I will add two more factors that are associated with predatory publishers:

For instance, the MDPI journal "Vaccines" recently published a vaccine misinformation piece that falsely claimed more people suffered serious complications from Covid vaccination than from Covid-19 disease (amongst a long history of other controversial pieces summarized here). However other publishers have also published controversial pieces that clearly lacked the rigour of professional peer review (e.g. see Frontiers Media here and Bentham Open here), and even highly-respected journals can slip up every now and then: remember that Science article about Arsenic being used as a DNA backbone? It is thus imperative to come up with ways to quantify the degree of predatory behaviour beyond anecdotes.

IF/SJR: identifying Impact Factor inflation

Predatory publishing is a significant issue in scientific discourse. Predatory publishers erode the integrity of science in the public eye due to accepting poor quality work or even misinformation advertised as professional investigation, and harm scientists that contribute time and money to aid these disreputable companies. Recent conversations around the Multidisciplinary Publishing Institute (MDPI) have accused MDPI of engaging in predatory practices. Notably, MDPI journals have been observed with high self-citation rates, which artificially inflate their Impact Factor compared to honest scientific discourse. Here I use a novel metric to assess whether MDPI journals have artificially inflated their Impact Factor: the ratio of Impact Factor (IF) to SCImago Journal Rank (SJR). This IF/SJR metric readily distinguishes reputable not-for-profit publishers from a known predatory publisher (Bentham Open), and also from MDPI. I further included a spectrum of for-profit and non-profit publishing companies in the analysis, including Frontiers, BMC, and PLoS. My results inform on the degree of predatory publishing by each of these groups, and indicate IF/SJR as a simple metric for assessing a publisher's citation behaviour. I suggest that an IF/SJR ratio >4 is an indication of possible predatory behaviour, and scientists approached by publishers with IF/SJR > 4 should proceed with caution. Importantly, the IF/SJR ratio can be determined easily and without relying on data hiding behind paywalls.

Background

The full dataset and R scripts used for the analysis are provided as a .zip file at the end of this article.

Predatory publishing is a major issue in the scientific literature. Briefly: predatory publishers basically pose as legitimate scientific journals, but fail to perform the minimum rigour as curators of scientific information. Nowadays, outright fake journals are readily spotted by careful scientists, but quasi-predatory publishers can appear quite professional and are much more difficult to identify.

Quasi-predatory publishers are identifiable by a few key factors (I have selected a few factors discussed in Ref [1]):

- The journal may include articles far outside its scope.

- Timelines for publication are unrealistic.

- Spam emails frequently invite academics to submit papers, often to 'special issues' that occur far more frequently than regular issues ever do.

- Impact metrics are prominently advertised and appear as part of a "hard sell" to academics to show that their journal garners attention.

Regarding this fourth point, a journal's Impact Factor (IF) is an important metric that is used by granting agencies and scientists to judge a journal's prestige (for better or worse). The IF is determined by the average number of citations articles get when published in that journal. Importantly, the IF number can be artificially inflated by authors citing themselves or their close colleagues in a biased fashion [2]. On the surface, this gives the impression that the scientist or journal is highly productive and well-recognized. This gives predatory publishers a significant incentive to engage in self-citation practices that inflate their Impact Factor. Predatory publishers do this by citing work from their own network of journals in an unabashedly biased fashion [1]. I'll be referring to this as "Impact Factor Inflation" hereon (see [3]).

Analyses like this one and studies like this one [1] have already discussed the quasi-predatory or even outright predatory behaviour of MDPI, which has grown more bold and problematic in recent years. The recommendation of Ref [1] was that scientific journal databases should remove MDPI due to predatory behaviour, indicating the degree of the issue being debated with MDPI. In particular, MDPI was seen to have significant self-citation issues, alongside 'citation cartels', networks of journals that cite each other to artificially inflate their impact factor [1].

I will add two more factors that are associated with predatory publishers:

5. The publishing group is part of a "mega-publisher" business model that hosts tens or even hundreds of scientific journals.

6. A history of controversial publications that require retraction or editorial comment.

For instance, the MDPI journal "Vaccines" recently published a vaccine misinformation piece that falsely claimed more people suffered serious complications from Covid vaccination than from Covid-19 disease (amongst a long history of other controversial pieces summarized here). However other publishers have also published controversial pieces that clearly lacked the rigour of professional peer review (e.g. see Frontiers Media here and Bentham Open here), and even highly-respected journals can slip up every now and then: remember that Science article about Arsenic being used as a DNA backbone? It is thus imperative to come up with ways to quantify the degree of predatory behaviour beyond anecdotes.

IF/SJR: identifying Impact Factor inflation

Drosophila geneticists benefit from decades of research and development, providing tools that can tackle literally any gene in the genome. At the click of your mouse, you can readily order flies that will express dsRNA to knock down your gene of interest for <$20 plus the cost of shipping. Most genes have putative mutant alleles disrupting gene expression or structure. Now, in the age of CRISPR, it's even easier to fill in the gaps where existing toolkits are less robust.

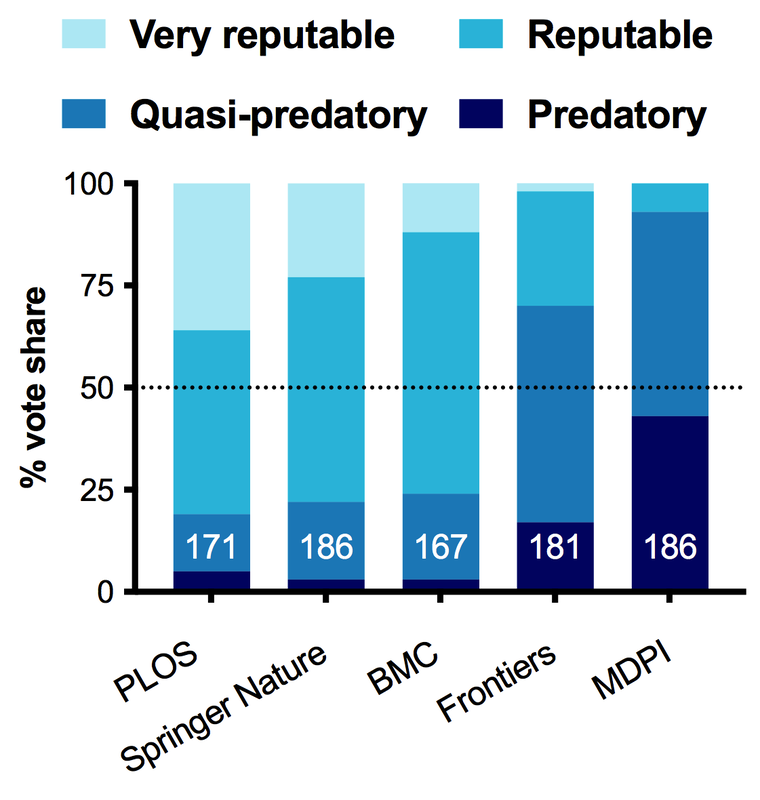

But CRISPR involves capitol. Time and money, and energy. And after that, there is still a chance that your "good" mutation isn't as good as you thought it was. Take it from someone who's experienced this firsthand on more than one occasion: and I haven't even worked with that many flies generated using CRISPR and double gRNA! Briefly: we generated and tracked a Cecropin mutation using mutant-specific primers, but somehow failed to detect a wild-type Cecropin locus present in our Cecropin-mutant stocks caused by a bizarre recombination event. More recently, I detected that a similar double gRNA approach that also included an HDR vector (two chromosome arms that were there as guides to the locus) did not insert as one might expect... I detected this after performing maybe the 3rd or 4th routine-check PCR where I eventually realized: "hey... that band is ~100 bp larger than it should be... isn't it?" In the end, instead of replacing the locus, the HDR vector failed to do its job and inserted in the middle of the promoter. SNPs and a 10 nt indel prevented detection by existing primers for the wild-type gene. In the end, our mutant was still effectively a hypomorph (which is good, because it had a phenotype we spent a good while on), but not a full knock out (Fig 1).

But CRISPR involves capitol. Time and money, and energy. And after that, there is still a chance that your "good" mutation isn't as good as you thought it was. Take it from someone who's experienced this firsthand on more than one occasion: and I haven't even worked with that many flies generated using CRISPR and double gRNA! Briefly: we generated and tracked a Cecropin mutation using mutant-specific primers, but somehow failed to detect a wild-type Cecropin locus present in our Cecropin-mutant stocks caused by a bizarre recombination event. More recently, I detected that a similar double gRNA approach that also included an HDR vector (two chromosome arms that were there as guides to the locus) did not insert as one might expect... I detected this after performing maybe the 3rd or 4th routine-check PCR where I eventually realized: "hey... that band is ~100 bp larger than it should be... isn't it?" In the end, instead of replacing the locus, the HDR vector failed to do its job and inserted in the middle of the promoter. SNPs and a 10 nt indel prevented detection by existing primers for the wild-type gene. In the end, our mutant was still effectively a hypomorph (which is good, because it had a phenotype we spent a good while on), but not a full knock out (Fig 1).

Figure 1: the BaraB[LC1] mutation (Hanson and Lemaitre, 2021) did not insert as expected. This mutation disrupts the promoter but the full gene remains present and mostly unchanged. A 10nt insertion at the C-terminus overlapped the reverse primer binding site that was initially used to check for the wild-type locus.

My point here is that CRISPR isn't a magic tool that always works. Beyond these bizarre instances, off-target effects are a serious concern and could affect 4% of CRISPR mutant stocks (Shu Kondo, EDRC 2019); or more, it's tough to say! In total, CRISPR is a powerful tool in the toolkit, but it requires gRNA generation, injection, mutant isolation, and in my experience something that is especially important: robust mutant validation. This process takes a couple months at best, but more likely longer. But what if you didn't have to make new mutations? What if there was already an existing mutation you could access, but not in known databases.

Enter the DGRP

Author

Mark

Archives

March 2024

March 2023

February 2023

October 2022

April 2022

December 2021

October 2021

March 2021

June 2020

November 2019

RSS Feed

RSS Feed